- About

- Programs

- Resources

- For AFT Higher Ed Members

- Academic Freedom

- Shared Governance

- Political Interference in Higher Ed

- Racial Justice

- Diversity in Higher Ed

- Responding to Financial Crisis

- Privatization and OPMs

- COVID-19 Pandemic

- Contingent Faculty Positions

- Tenure

- Workplace Issues

- Gender and Sexuality in Higher Ed

- Targeted Harassment

- Intellectual Property & Copyright

- Free Speech on Campus

- Civility

- Publications

- Data

- News

- Membership

- Chapters

Budget and Finance Rucksack

Tools and resources for tackling austerity.

As coeditors of this Academe special issue on revolutionizing higher education budget and finance, we have prepared an information-stuffed “rucksack” to demystify the jargon, assumptions, and practices of financialization on our campuses. It provides individual and collective tools that faculty members, staff, students, and alumni can use to analyze campus finances, challenge austerity practices, and engage in budget activism to build alliances and organize for change locally and statewide.

The rucksack proposes steps toward a long-term organizing strategy, which is key to leveraging power to challenge the distribution of funds and reverse the trend of financialization. It expands on ideas shared by Aimee Loiselle in February 2021 on the Labor and Working-Class History Association Contingent Faculty Committee Blog.

Part 1—Glossary of Key Terms

capital outlay. Money spent to maintain, upgrade, acquire, or repair capital assets; sometimes called capital expenditures. Capital outlays are recorded as liabilities on balance sheets but considered investments, so the accounting is different from that for operational expenses.

deferred compensation. Remuneration received at a later date, including individualized investment plans for top administrators in addition to conventional retirement contributions. A board may allocate hundreds of thousands of dollars a year in deferred compensation, which can be invested tax-free until the time of the payout; for example, the president of Johns Hopkins University received in 2013 $1.6 million in salary, $1.1 million of it in deferred compensation, and $310,000 for serving on the board of directors of T. Rowe Price, while the CEO of that investment firm served on Johns Hopkins’s board of trustees.

“Counting Deferred Compensation"

financialization. The increasing influence of financial advisers and firms over institutional policies and practices, which elevates the financial sector and transfers resources and capital from other areas, like teaching, into the drive for short-term gains.

highest return on investment (HROI). A measurement used in budget models that emphasize capital revenue, evaluating the financial performance relative to the amount of money invested. Return on investment (ROI) is the ratio between net income over a period of time and investment or costs at a particular point in time; a high ROI means the investment’s gains over time compare favorably to its cost. As a performance measure, ROI is used to evaluate the efficiency of an investment or to compare the efficiencies of several different investments or costs.

incentive-based budgeting (IBB). A current budget model that administrations use to replace the “incremental” budget process (in which a prior year’s budget is carried forward with annual increases or decreases based on costs and resources). IBB is based on anticipating multiyear university changes, mostly to enrollment and tuition, and top priorities, usually financial. It pushes financial responsibility downward onto departments, now called “revenue centers,” which have to track and often generate their own income and determine their own expenditures.

“IBB 101 and UVM,” University of Vermont United Academics, April 2019

“Incentive-Based Budgeting,” Purdue University Northwest

online program management (OPM). The process, technology, and providers associated with web-based higher education delivery platforms. Technology, enrollment, and operations leaders at institutions use OPM partnerships to enable e-learning and comprehensive online services instead of building their own in-house services.

“Demystifying Online Program Management,” Focused Solutions

operational expense (OPEX). Expense incurred through normal business operations, including rent, equipment, inventory costs, marketing, payroll, and insurance.

outsourcing. Payments by public and private nonprofit colleges and universities to outside for-profit entities to create and operate bookstores, dining and custodial services, and online courses; recruit and enroll students; advise and tutor students; provide mental health counseling; manage research, IT, and utilities; and build or manage dorms, classrooms, labs, parking, and student unions

“More Colleges and Universities Outsource Services to For-Profit Companies,” Hechinger Report

president’s cabinet. An administrative model that sometimes undermines or replaces shared governance and institutional deliberative processes through reliance on a core “cabinet” of vice presidents, officers, and hand-picked senior deans and faculty advisers who guide major decisions, particularly regarding budgets and finances (for example, American University Cabinet and University of Maine Cabinet).

public-private partnerships (PPP). Arrangements made by public-sector entities, including colleges and universities, with private for-profit companies to provide services or educational programs (see also “outsourcing” above). The risk and funding of PPPs are carried by the public institution, while the private companies have contracts to receive payment regardless of outcomes, most often resulting in a major transfer of public wealth to private investors.

“How the Right PPP Provides Value,” EY Parthenon

resource optimization. Narrow, financial data–driven, campus-wide effort to extract as much service and teaching as possible, with attention to enrollment trends and in response to reduced state funding. Board or administrative leadership objectives for resource optimization often involve prioritizing student enrollment numbers and operational “efficiencies” as ways to increase revenues and cut expenses, yet divorce this narrow data from teaching, advising, and service conditions and their significance for student success and completion.

“ROI Campus Forum: Making Efficient Use of Department Budgets,” University of Central Arkansas

responsibility-centered management (RCM). Type of IBB in which academic units are responsible for their own costs and for generating their own revenue, with academic units often having to share a portion of this revenue with the central administration to cover institutional overhead. Revenue that academic units generate beyond their costs and the portion shared with the central administration is the academic unit’s to “reinvest.” RCM encourages competition, rather than collaboration, for enrollment and tuition and incentivizes outside grants and private funding through a constant emphasis on the need to generate revenue. Authority for academic matters shifts to deans and unit leaders, with the goal of “efficiency” and an “entrepreneurial mindset.”

“Budgeting Institutional Success,” American Council on Education

“Responsibility Center Management,” University of Alabama

“Understanding the Rutgers Budget Swindle,” Rutgers AAUP-AFT

shared services. New service delivery models in which departments and units reduce costs by sharing staff, funds, and equipment in ways that maintain minimum compliance with ADA, state, and federal requirements . As campus budgets tighten and funds shift to central administration and finance management., this model is often presented to academic departments as a means of retaining control while cutting costs, however, staff is usually stretched out and overloaded.

“Shared Services: Finding Right Fit for Higher Ed,” Huron Group

“Shared & Business Services in Higher Education,” SSON: Shared Services & Outsourcing Network

“What Does It Mean to Share Services?” University of Washington

Part 2—Basic Steps for an Organizing Strategy

A. Form a core group of faculty and staff committed to both budget research and using the results for organizing a larger campaign such as a university-wide or AAUP chapter budget action committee. Options for where to focus your budget research include the distribution of budget cuts over the previous decade; costs and liabilities for massive construction projects; cuts in spending per student; loss of full-time faculty and staff and the cost to return them to full time; outsourced services and loss of services with costs; total salaries and compensation for administration and coaching staff; costs for financial consultants, bank fees, and debt financing; money spent on commercial real estate; expenses for consultants (for example, SimpsonScarborough and Huron Group); the way the administration has used certain grants or federal funds; the role of private donors; how many professors or staff could be hired with funds spent on frivolous projects or coaches; and so on.

B. Find your campus budget information. All campus budgets use language and reporting practices that mystify the content even as they express an interest in transparency. Public institutions must publish budgets and annual reports with details. Private institutions do not have the same level of obligation, but they must offer financial reports and keep records.

For public institutions, search for your campus name and “budget” and “financial report” (see, for example, Budgets and Financial Reports, University of Massachusetts Amherst). You can also find some reports for boards of trustees and regents.

For private institutions, search for your campus name and “budget office,” “financial planning,” or “financial audit” (see, for example, Budget Office, Stanford University). Depending on the extent of your institution’s transparency, you might have to dig deeper and combine reports from boards of trustees and alumni fundraising groups.

Additional reading:

“Financial Reporting in Higher Education,” Hanover Research, 2014

“Guide to Analyzing University & College Financial Statements,” Canadian Association of University Teachers, 2016

C. For a public higher education system, find statewide budget information.

- Searches with your state’s relevant administrative office names and keywords such as “secretary of higher education,” “board of higher education,” “legislative committees,” and so on. There are also helpful newspaper articles each year about state legislatures and higher education funding bills (for example, “Lawmakers Reach $3.5 Billion Higher Ed Deal,” The Center Square Minnesota).

- National organizations such as the Education Commission of the States, the National Association of State Budget Officers, and the State Higher Education Executive Officers Association (SHEEO), which publishes the State Higher Education Finance report, are also resources for state-level information on education legislation and budgets.

- Locate analytical white papers and reports about your state; many of these will already have recommendations that await the necessary long-term organized pressure to push for required legislative or regulatory changes.

See “Reverse the Course: Changing Staffing and Funding Policies at Massachusetts Community Colleges,” July 2013. It contains funding and student information and offers proposals for addressing various funding problems. On page 15, it provides an analysis of how state budget practices exacerbate adjunctification.

In the 1970s, the Massachusetts state government wanted to encourage community colleges to offer evening and weekend classes taught by professionals. It established Division of Continuing Education (DCE) faculty as opposed to full-time tenure-line faculty in the Day Unit. Tuition generated by all classes taught by DCE faculty (adjunct professors) would be held on the campus, while tuition from classes taught by Day Unit faculty continued to go to Boston for the state budget. At first, this worked: in the 1970s, evening classes expanded, with new classes in accounting, paralegal training, and so on. But during the 1980s to 1990s, and accelerating in the 2000s, this arrangement led to more adjunctification with DCE faculty teaching most daytime classes, without legislative changes to authorize that shift. DCE faculty teach approximately 70 percent of classes held at all times on all community college campuses—not simply because they’re cheaper to hire on a per-class basis but also because they generate on-campus revenues during a time of austerity.

· Your state’s legislature may also have a legislative analyst office with research and resources (for example, see the California Legislative Analyst’s Office’s 2022–23 California Spending Plan: Higher Education).

D. For private higher education, find endowment information. Research should look beyond the size of the endowment and investigate target restrictions on the endowment, what firm or office manages it, where it is invested, and fees paid to outside investment managers. We’ve entered a world where, instead of having an endowment to support a university, the university serves as a tax shelter for the endowment. See Endowment Report 2020 from Dartmouth College.

And public universities often have endowments too!

Additional reading:

Robinhood, “What Are University Endowments?” 2020

Association of Public and Land-Grant Universities, “Public University Endowments,” 2019

Thomas Gilbert and Christopher Hrdlicka, “A Hedge Fund That Has a University,” Wall Street Journal, November 13, 2017

Kelly Grotke, “Failure of Financialized Higher Ed,” American Prospect, September 2021

David Rosowsky, “Why Not Use Those Large Endowments to Save Colleges?” Forbes, June 1, 2020

Casey Williams et al., “How Student Activists at Duke Transformed a $6 Billion Endowment,” The Nation, January 25, 2014

Part 3—Building Budget Activism

A. COALITION BUILDING: Use the budget basics and information your group or committee has gathered to build a coalition with other campus workers, students, and community allies. Create a group or committee social media account on Twitter, Instagram, or other platforms to get started with basic outreach, “following” your potential coalition partners, and sharing some of your information and data.

- UnKoch My Campus has webinars on coalition building for budget activism.

- Scholars for a New Deal for Higher Ed (SFNDHE) and the AAUP have a series of webinars on budget activism and coalitions.

- The spring 2021 issue of Academe has an article on the efforts of Rutgers AAUP-AFT to build a coalition across various unions on its campus.

- See Building Campus Coalitions, AAUP.

B. FORENSIC AUDITS: If your group or committee has the resources and formal standing to commission a forensic audit of your campus budget, it’s an extremely valuable investment. Faculty at Rutgers University, SUNY Buffalo, the University of Arizona, Johns Hopkins University, and other institutions have hired Howard Bunsis of Eastern Michigan University, an AAUP member and former leader. Faculty at Mills College and Saint Xavier University hired Matthew Hendricks of University of Tulsa.* Auditors produce a report or online dashboard that shows the specific usage of campus financial resources (look out for an article by Hendricks on data dashboards in the forthcoming online supplement to this issue of Academe). Such audits provide useful information for budget mobilization and new ways to visualize, share, and deploy the knowledge.

C. CONTINGENT LABOR:

(i) Use the budget information to calculate how much the institution spends on faculty members with contingent appointments and how much the institution earns in tuition from the courses they teach. Calculate how much it spends on tenure-track and tenured faculty members and how much it earns in tuition from their courses. Depending on your campus, you might break down numbers to compare part-time contingent adjunct faculty, full-time contingent contract faculty, and tenure-track and tenured faculty.

(ii) If your group or committee has the resources, you can research how much it would cost to turn all contingent instructors into full-time employees. Administrations often argue that they cannot afford it, but the costs are usually a small percentage of the budget. It helps if someone on your team has business or human resources experience.

Defense and expansion of tenure as a “labor protection” remains an important long-term goal for higher education activism. However, this budget action focuses on the short-term goal of conversion of part-time contingent positions to full-time positions.

(iii) Tie these budget actions to collecting personal stories. These can be anecdotes from adjunct faculty members or, for example, photographs of them with signs that state “I’m an adjunct at ______ and I earn $ _______ for _____ classes” or “I’m a lecturer at _________ teaching _____ classes but I have to work at _____ or get food stamps to survive.”

D. DONORS: UnKoch My Campus is an established organization with its own toolkits. It’s committed to exposing the influence of private and corporate donors that “are exerting undue influence on colleges and universities nationwide to further a corrupt agenda that centers corporations and roll[s] backs social and economic progress.”

You can use its tools and advice for submitting Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests, or establish a campus campaign with its support, like campaigns at UNC Chapel Hill, Wake Forest University, College of the Holy Cross, Penn State University, and George Mason University.

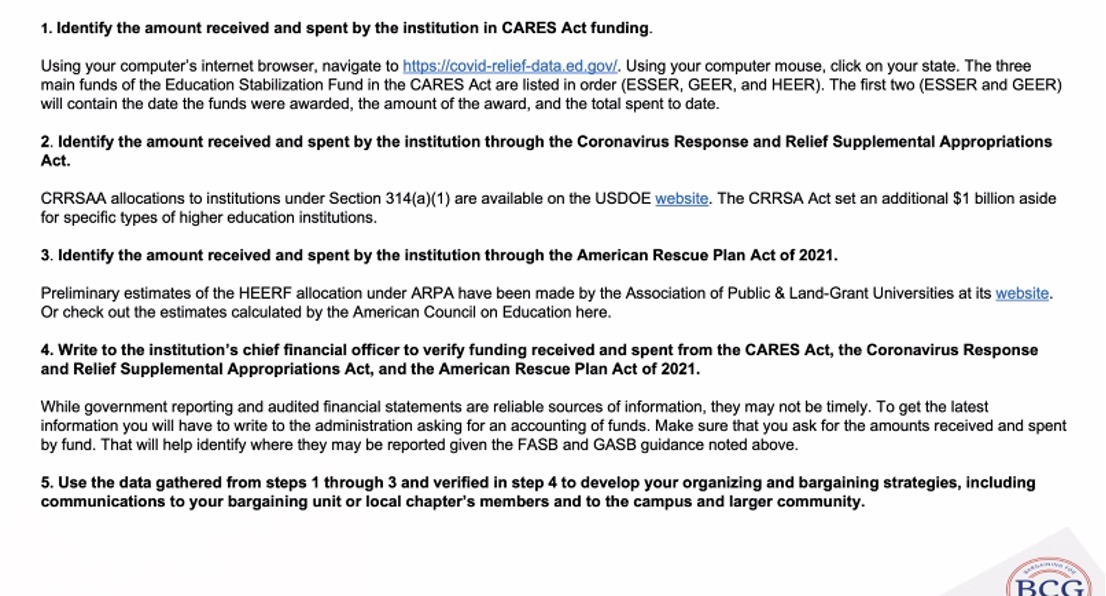

E. CARES ACT AND HEERF FUNDS: Track and calculate how your institution received and spent federal pandemic aid from the 2020 Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act and three rounds of Higher Education Emergency Relief Fund (HEERF). (See screenshot below with step-by-step instructions from Bargaining for the Common Good.)

F. INSTITUTIONAL DEBT: Using the institutional debt toolkit from the Debt Collective and Public Higher Education Workers (PHEW), calculate the college or university’s debt load and its annual debt financing costs. Then use that number to formulate persuasive statistics that can be used as organizing tools such as how many adjuncts could be converted to full-time or tenure-track positions with these funds, how much of this debt financing is carried per student (that is, average cost of debt per student), additional course sections that could be offered using the debt financing funds, and so on.

G. ADMINISTRATOR COMPENSATION: Investigations of administrator compensation should address salaries and deferred compensation and should be tied to evidence of the failure of these highly compensated professionals to be effective or creative at their top imperative: managing financial risk. Research the combined salaries and deferred-compensation liabilities for top administrators and the ties between presidents and vice presidents serving on boards of directors and donors on institutional boards of trustees. Budgetary analysis is more effective than simply listing salaries.

This example of management bloat comes from Bunsis’s analysis of Rutgers University: “Rutgers reported 312 senior managers earning a total of $65.3m in 2018–2019, up from 292 earning $57.4m only two years before. There are at least 37 senior managers and coaches earning over $350,000 yearly. Beyond management’s own salary expenses, the university reports spending $285.7m on ‘General administration and institutional support’ overall.”

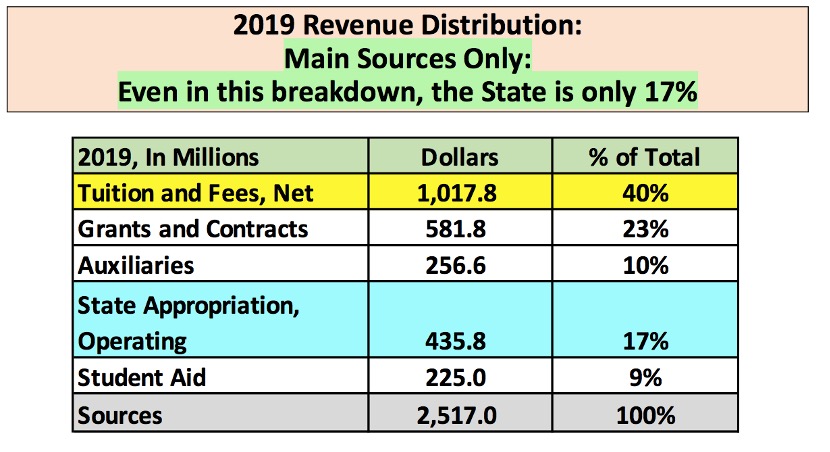

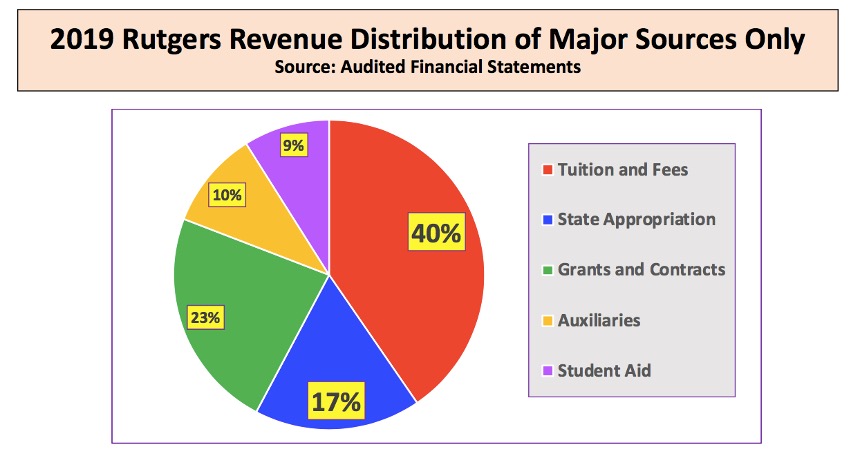

Matthew D. Hendricks, “The Plight of Mills College Should Be an Alarm,” American Prospect, April 2022

H. DATA VISUALS: Using budget information and institutional financial reports, calculate figures related to the priority issues for your particular group or committee. Use your research to make effective visuals—great for teach-ins, social media, outreach to allies, op-eds, and articles in local publications—to raise awareness, trigger outrage over the budget realities, build your coalition, organize, and plan future demands. These are tools that must be put to creative use; the information on its own is usually not enough to change administrators or legislators, but effective visualizations can persuade allies and voters and help build leverage. Below are two examples for Rutgers.

Part 4—From Mobilizing to Organizing to Making Demands

A. Develop a plan for using the budget research to engage in action. Outreach should bring in more members to your group or coalition and raise public awareness, thereby enabling you to recruit even more members. Mobilizing is getting people who already care about the issue to become more active. Organizing is setting an active agenda, outlining goals and action steps, and determining your leverage and what steps are feasible (for example, a faculty and staff slowdown or work-to-rule, sit-in, building occupation, alumni donation boycott, action targeting the board of trustees or regents, walkout or strike, endorsing state candidates, inviting accrediting agencies to investigate and enforce criteria, and so on). The ultimate objective of organizing is to build countervailing power as leverage when contacting state legislators or making demands on upper administrators.

i. Launch a public outreach and awareness campaign. Attract supporters and build public pressure on legislators and administrators. Use the budget data to articulate core demands: shaming administrators or legislators with public announcements is a helpful tactic if you have significant public buy-in, a link to specific policy proposals, and a counterweight or leverage, but it does little without such official proposals and the ability to inflict some pain on administrators or legislators.

ii. Create a core presentation you can give to a variety of audiences. Give the presentation at student events, allied faculty or staff group meetings, alumni events during a major weekend like homecoming or reunion, town or city events or potential ally groups, public libraries, or state senators’ and representatives’ offices.

iii. Create a series of press releases for local and regional newspapers with aligned social media posts.

B. Seek allies at institutions across the state and establish a regional or statewide committee on budget needs for quality higher education; meet to compile formal quantitative and qualitative state budget recommendations with firm number proposals. Find the relevant government entities, like the legislature’s joint committee on higher education, the secretary of education, or board of higher education; submit official proposals with data, and then request meetings with these entities to present your demands and proposals.

C. Launch a petition drive on your campus, across your public system, or with statewide voters, depending on your ultimate goal. Use an online platform for gathering signatures and give people a script for calling all legislators.

D. Make a proposal to the upper administration with specific demands tied to an alternative budget. Do this after your group has a plan for its most effective escalation of consequences (for example, from demonstrations to an alumni donor boycott to an organized strike, if possible).

Part 5—Additional Resources

Articles

Eaton, Charlie et al. “Borrowing Against the Future: The Hidden Costs of Financing U.S. Higher Education.” Debt & Society, 2014.

Furstenberg, François. “University Leaders Are Failing.” Chronicle of Higher Education, May 19, 2020.

Newfield, Christopher. “Budget Justice.” Academe, Spring 2021.

Schirmer, Eleni. “It’s Not Just Students Drowning in Debt. Colleges Are Too!” The Nation, November 20, 2020.

Welch, Nancy. “Educating for Austerity.” International Socialist Review 76 (March 2011).

Welch, Nancy. “La Langue de Coton: How Neoliberal Language Pulls the Wool Over Faculty Governance.” Pedagogy 11, no. 3 (Fall 2011).

Books

MacLean, Nancy. Democracy in Chains: The Deep History of the Radical Right’s Stealth Plan for America. New York: Viking, 2017.

Welch, Nancy and Tony Scott, eds. Composition in the Age of Austerity. Logan: Utah State University Press, an imprint of the University Press of Colorado, 2016.

Video and Audio

“Budget Crisis at Some Universities Made Up.” August 2010. Voices of the AAUP video, 7:26.

“Higher Education: Building Civil Societies through Common Good Bargaining.” Video, 1:25:12.

A. Melissa Case (National Education Association), sharp budget analysis used for bargaining, 34:20–47:54 (guidance on CARES Act analysis 44:32–47:54).

B. Rich Levy (Salem State University), example of a faculty group using budget activism with institutional debt, 49:01-1:05:23.

“Endowments: If Not Now, When?” Residential Spread podcast, 50:27.

Discussion of endowments with focus on how private equity firms are making money from higher education.

“Making the Invisible Visible: University Institutional Debt.” Videos, two hours.

The *Other* College Debt Crisis—Consortium Contacts

A. Introduction (video 1)

B. Explore Our Institutions’ Debt Service with Rich Levy and Joanna Gonsalves, Salem State University

C. Identifying the Infrastructure: Researching College and University Debt with Bargaining for the Common Good and Service Employees International Union (SEIU) Local 1021 (video 2)

D. How and Why Debt Audits Can Be Useful and Empowering with Andrew Ross, New York University (video 3)

E. Debt is the Lifeblood of Late Capitalism with Louise Seamster, University of Iowa) (video 4)

f. Exposing the Contradiction: Campaigning Against Debt with Corey Sherman, SEIU Local 1021 (video 5)

g. Closing with Jason Wozniak, West Chester University (video 6)

h. Spreadsheet of Institutional Debt

Inside the Opposition

“Incentive-Based Budget Guide.” University of Wisconsin, Green Bay, 2019.

“Governance for a New Era: A Blueprint for Higher Education Trustees.” American Council of Trustees and Alumni, August 2014.

“Moody’s Investors Service: Higher Education”

“Why RCM, How Does It Work: Model Structure at Drexel University.” Drexel University, 2020–2021.

Grawe, Nathan D. The Agile College: How Institutions Successfully Navigate Demographic Changes. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2021.

Allies for Academic Labor

American Federation of Teachers (AFT)

Higher Education Labor United (HELU)

Princeton Anti-Austerity Coalition

Public Higher Education Workers (PHEW)

Scholars for a New Deal for Higher Education (SFNDHE)

SEIU Faculty Forward

Aimee Loiselle is assistant professor of history at Central Connecticut State University. Jennifer M. Miller is associate professor of history at Dartmouth College. They are members of Scholars for a New Deal for Higher Education.

* Academe editorial staff added “Faculty at” to this sentence as a clarification following the article's publication.