This story begins in April 2020. Scarcely a month had elapsed since the pandemic shut down Johns Hopkins University’s campuses, but university leadership was panicking, envisioning losses in the hundreds of millions of dollars.

In response to the alleged threat, the university president announced several “broad-based and decisive austerity measures.” The first—projected to save the university $100 million—froze contributions to employee retirement accounts. Employee furloughs and layoffs would follow, he declared, along with other dramatic cuts.

Initially, faculty were too preoccupied responding to the health crisis and managing the transition to virtual learning to respond. As the semester wound down, however, resistance began to grow. When one of the authors of this article, François Furstenberg, published an essay questioning the competence (and pointing to the bloated salaries) of a senior administration better suited to a corporate boardroom than a university seminar room, the response surprised us both.

Emails poured in from faculty at Hopkins and other universities. Many wrote to express a common sentiment: this is not the university system I entered forty, thirty, or even twenty years ago. They felt that today’s university had become unrecognizable, transformed by the corporatization of higher education that other contributors to this issue of Academe, including Davarian Baldwin and Colena Sesanker, describe. Ultimately, their anger helped spark a broader response with repercussions that continue to echo today.

Is it ironic that several years of lackluster effort at faculty organizing at JHU finally took off for self-serving reasons? Those with more experience in organizing may find nothing strange here: that budgetary issues—an area of university governance where the voices of administrators generally prevail—prompted the first successful challenge to the president’s style of decision-making.

A Corporatized University

It was in 2009, with the arrival of a new university president, Ronald J. Daniels, that JHU’s slow drift toward administrative centralization shifted into high gear. Determined to overhaul an institution where faculty had long played a strong governance role, President Daniels made centralization under the mantra of “One University” a cornerstone of his agenda. Gradually, the locus of strategic decision-making and day-to-day governance shifted from deans and faculty to the president’s “cabinet,” made up of a cadre of selected subordinates.

Traditional centers of power—including deans, faculty, and student groups—withered under the pressure. The president reconfigured the board of trustees to strengthen his power and dismissed divisional deans and a succession of provosts. The message was clear: deans serve at the president’s pleasure. Several excellent deans left or were forced out, and new ones found their jobs immeasurably harder.

Detached from the faculty, President Daniels surrounded himself with a burgeoning staff of advisers, deputies, and vice presidents, nearly all of them culled from the realms of finance, law, and business. Alongside the university’s trustees, they have served as his sounding board in developing institutional policy. Few with access to the president know much about the university’s teaching and research mission.

Initial faculty pushback was ad hoc and largely ineffectual. Disregarding widespread anger, for example, the president successfully pushed through a controversial reform to give himself a greater role in tenure decisions.

Around the same time, the Homewood Faculty Assembly, which represents faculty in the arts and sciences and engineering schools at the university’s main “Homewood” campus, called a special meeting to ask the president about reports that, on a single day, ten senior Hopkins officials donated a total of $16,000 to Baltimore’s mayor, Catherine Pugh, who was later sent to prison for corruption. The president attended but ignored the questions.

Most consequential of all was the president’s determination to push through the state legislature a law chartering a private police force for the university. As Davarian Baldwin discusses in his interview with Jennifer Mittelstadt in this issue of Academe, such moves inevitably alienate nearby residents. A group of faculty members mobilized a petition opposing the police force but collected a mere hundred signatures. No one seemed to have the leverage to persuade the administration to rethink its decisions—not even the wave of nationwide unrest after the police murder of George Floyd in 2020 could do more than “pause” the president’s plans.

Surprisingly, it was a budget challenge that finally sparked a level of organizing that could counteract the president’s executive style. The lesson we take away from that episode is this: pocketbook issues matter. Although they may seem self-serving, they are useful tools for organizing faculty, building coalitions, and challenging expansive administrative power.

More important, perhaps, budgetary issues open a door to reinsert faculty and staff into institutional decision-making and to establish a better equilibrium in university governance. They can strengthen the role of the faculty in the three-legged governance structure set forth in the AAUP’s joint Statement on Government of Colleges and Universities—restoring some balance between and among board, administration, and faculty.

Austerity Cuts Raise Bigger Questions

As in the situation at the University of Tulsa that Matthew Hendricks describes in a forthcoming online supplement to this special issue of Academe, Hopkins leadership had used the pandemic to announce cuts to advance a policy of fiscal retrenchment that hit the lowest-paid employees hardest. (How anyone could possibly have reliable financial estimates so early in the pandemic is another question.)

It’s possible that a broader effort to share financial information and deliberate with the faculty might have resulted in this same radical decision. But the upper administration didn’t think they had time for such consultation, and it was hardly the president’s style.

Furstenberg’s essay stirred long-simmering embers of anger and frustration at Hopkins, and those feelings were not limited to the arts and sciences faculty. Medical faculty were the most infuriated, perhaps because they had been subject to the corporatization of their work lives even earlier and were making enormous sacrifices to control the damage wrought by COVID-19.

A week later, a faculty petition to the president and board of trustees denounced the austerity measures, especially the process “which perpetuate[s] a pattern of unilateral decision-making.” It called for more information about university finances and demanded immediate steps to include faculty elected to participate in all levels of decision-making. In a few days, the petition got six hundred signatures—a remarkable number compared to previous efforts.

As summer 2020 began, the faculty assembly of the engineering and arts and sciences schools called several extraordinary meetings. The transition to virtual meetings on Zoom allowed hundreds, including faculty members from other divisions, to attend. Discussion in these forums raised numerous questions: If the stock market collapse in March justified the pension freeze, why was the market rebound in the late spring not calling that policy into question? When and under what conditions would the university resume its pension contributions? Did the freeze violate faculty and staff contracts?

Such questions highlighted the insular nature of institutional decision-making since administrators wouldn’t provide answers to basic questions. Could it be that excluding faculty and staff voices led to poor decisions?

Faculty discussions soon moved beyond pensions to broader questions: How are budgets determined? Why are elected faculty members not included in the process of budgeting? Are members of the president’s “cabinet” and trustees—who make the decisions—too detached from teaching and research to understand the trade-offs involved in their budgetary decisions?

One professor said faculty wanted “a conversation about how budgeting happens in the first place.” Like the alumni and faculty discussed in Kelly Grotke’s article in the online edition of this issue of Academe, many agreed. The issue was bigger than just pension cuts—or even budgeting. “How are we going to re-center genuine faculty governance?” asked another faculty member.

It became evident that misfires over pension freezes and the controversy over the university’s police force were symptoms of the same issue: the university’s hierarchical structures had become too centralized and opaque. Could we develop an institutional governance structure in which the president and “cabinet” felt as accountable to faculty, staff, and students as they did to the board of trustees?

The discussions even questioned the board’s composition. Perhaps, mused a faculty member, “we also need faculty members as voting members on the board of trustees.” It was this shift to a broad analysis of the institution, we believe, that ultimately sparked action from the base.

Faculty Finally Push Back

The president had long resisted including faculty leaders in major university decisions. But he had a keen sense of power: when to push aggressively and when to relent. This was a time to relent.

The university announced the formation of a University Pandemic Academic Advisory Committee that would bring faculty leaders together with the president, provost, senior vice president for finance and administration, and deans. Although it remained advisory, and though members were often brought in at the eleventh hour to offer opinions, faculty representatives sitting in the body reported that their views did seem to matter.

Meanwhile, the provost convened several town halls to share financial information. Many felt the town halls—highly mediated settings in which questions were submitted and vetted ahead of time—were largely performative damage control. Nonetheless, the existence of such forums seemed notable.

Behind the scenes, other glimmers of change appeared. Although the upper administration had long convened a Faculty Budget Advisory Committee (FBAC) to give feedback on its financial decisions, it was not an institution of shared governance. Composed of faculty members carefully selected by deans and the provost and serving undefined terms, the committee met privately. No minutes of the unelected committee discussions ever circulated. Administrators did not ask for approval from the FBAC, nor were votes ever taken on their decisions.

But soon after the pandemic began, minutes of FBAC meetings were publicly posted. The faculty chair of the FBAC reported that he even began meeting with the president every other week. After having never had such access in the past, he marveled that he now had a hand in setting the agenda for FBAC meetings!

Although these piecemeal changes were welcome, they did not stamp out the faculty’s anger and did not constitute substantive shared governance. The hidden nature of the university’s budget had bred unrelenting frustration. Faculty critics pointed out that the president excelled at fundraising and oversaw billions of dollars in endowment growth. Where was the money going? If Hopkins had become so rich, why was it among the first universities to announce such severe austerity measures?

During those summer meetings, some faculty members floated the idea of a “forensic audit.” They knew of a professor of financial accounting at Eastern Michigan University, Howard Bunsis, who had done similar analyses at other institutions, using publicly available information (including tax filings, audited financial statements, and credit bureau reports) to compile revealing reports about a university’s financial condition. A vote on the idea resulted in the creation of an audit committee.

Meanwhile, a smaller group of faculty members from across seven of the university’s eight divisions formalized their meetings as an interdivisional committee approved by the Homewood Faculty Assembly. As its first task, the “InterDiv Committee” solicited funds to pay for the forensic audit. With an organizing network stretching through departments and faculties across the schools, the money poured in. In just three days, the necessary funds were raised.

When Bunsis presented his results in December, the impact was far greater than most of us had anticipated.

A Forensic Audit Stuns

With a no-nonsense presentation liberally sprinkled with baseball metaphors, Bunsis dismantled the university leadership’s justification for suspending pension contributions.

He showed that the university’s initial estimates of shortfalls were wildly exaggerated. Infuriatingly, the university had ended the fiscal year with a $75-million surplus. The university’s financial gurus had estimated losses of $51 million; they were wrong by $126 million! It was more than all the money saved by the pension freeze.

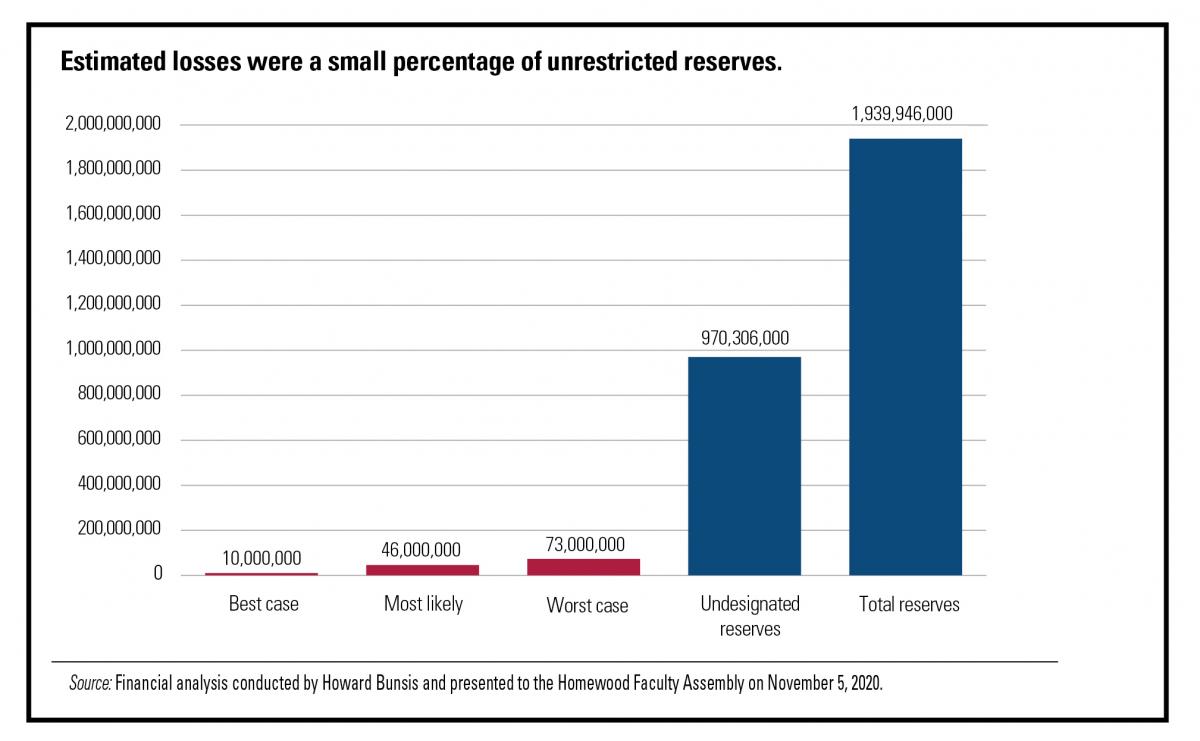

But that wasn’t all. In March 2020, university leaders had projected a staggering deficit of $475 million over fifteen months. The reality came nowhere close. Bunsis’s less hysterical estimates ranged from a best-case loss of $10 million to a worst-case scenario of $73 million. Either way, such losses could easily be covered by the university’s unrestricted reserves, which amounted then to nearly $1 billion (see figure below).

The financial analysis provided convincing evidence that the cuts to retirement contributions were unnecessary. Had the university decided against using reserves to cover the unexpected costs related to the pandemic—which is, after all the purpose of holding reserves—it could easily have borrowed the funds. Given rates prevalent in 2020, Bunsis pointed out, the cost would not have exceeded $5 million, a small amount for an entity with $6.5 billion in assets.

Bunsis didn’t stop with the pension cuts. He raised alarming questions about financial management more generally. He noted, as Grotke does in her article about Oberlin, that the university’s endowment tilted heavily toward the riskiest and most opaque investments. While investments in illiquid assets put the university on particularly precarious footing in the event of crisis, the increased risk had resulted in no greater returns. At a time of soaring financial assets, the Hopkins endowment had underperformed both its peers and the US stock market.

Finally, the audit, like the data dashboards Hendricks discusses in his forthcoming online article, highlighted the extraordinary growth in managerial positions at the university—which far outpaced the expansion of faculty or students. While management salaries were largely in line with those of our peers, faculty salaries lagged far behind.

What emerged from the audit findings was a sense that the university’s unelected and increasingly unaccountable leaders were not prudent stewards of the institution. The audit underscored the urgent need for more transparency in university finances and for the inclusion of elected faculty members in university governance.

With the audit published, the InterDiv Committee launched into action. In collaboration with the Audit Committee, we created a survey to ask faculty for feedback on the audit, using our network across divisions to ensure adequate outreach. The process also helped disseminate the findings.

Survey feedback came back in late January 2021. “Wow,” wrote one respondent, “there was so much in the slides that I reviewed that made me very angry and contributed to my ongoing low morale.” The survey results highlighted a broad loss of faith in the university’s senior leadership and declining faculty morale under the grueling pressures of the pandemic. Many respondents called for an expanded role for faculty in governance bodies, including the board of trustees.

The InterDiv Committee presented the audit findings and survey to faculty across the divisions. We encouraged faculty senates to pass resolutions calling on the central administration to restore pension contributions. We also encouraged sharp questions about the institution’s governance.

Finally, we scheduled a meeting with the university provost and interim vice president of finance. We pointed to the breakdown of trust between faculty and administration, and we emphasized that current structures of university governance were not serving the institution well. Excluding faculty from decision-making wasn’t only a matter of violating norms of governance: it was also leading to poor financial outcomes.

The results were impressive. Over the next few months, the university completely reversed course. In February 2021, it announced it would resume pension contributions retroactive to January 1, 2021—six months ahead of schedule. In April, it announced the reimbursement of employees for the six months of lost pension contributions in 2020.

If this reimbursement was a success on the immediate issue, the broader implications for faculty organizing were clear. The pension issue had pushed faculty members to ask bigger questions about financial stewardship and university governance. Ensuring the university’s health and preserving its mission would require more faculty involvement at all levels.

Building on a Win to Push for Shared Governance

Over the course of the two academic years from 2020 to 2022, the InterDiv Committee continued its weekly Zoom meetings. The group of twenty-five to thirty-five included faculty members from nearly all JHU divisions, many of whom had served in their local senates. Two former provosts regularly attended as well.

Meetings were informal but focused. Naveeda Khan, our convener, invited possible topics for conversation. Occasionally, guests visited for discussion on specific topics. A lawyer gave a presentation on the national landscape of faculty organizing. Faculty members from other institutions shared their experiences. We convened a panel on the history of faculty governance at JHU. The university’s vice provost for faculty affairs occasionally attended, while members of the University Pandemic Academic Advisory Committee regularly solicited feedback and suggestions.

Although it’s a relatively small institution, Hopkins is geographically dispersed, with campuses scattered across Baltimore and one in Washington, DC. The physical distances create acute barriers to faculty organization. They also result in an asymmetry between the faculty and deans and the university’s central leadership—the only group with a full bird’s-eye view of the institution.

As the InterDiv Committee learned about teaching and research across the divisions, we developed a better understanding of the broader institution. It would be hard to exaggerate how empowering it was to share the varied nature of our collective work, the mutual challenges we confront, and our hope for effecting institutional change. Appropriating the slogan of our centralizer-in-chief, we called our perspective “One University from below.”

Humanists in the room learned about the travails of faculty members in fields distant from their own. We heard how administrative centralization forces them to spend ever-greater amounts of time on management. Thus, a nursing professor who does extensive development work in West Africa explained her ordeals subcontracting with local organizations, forcing her underfunded local partners to work for months without pay because of impossible bureaucratic hurdles at JHU.

A natural scientist reported that every aspect of her research had become more time-consuming, harder, and less efficient. Some talked about the difficulties of hiring personnel with extramural funding, while others pointed to the growing complexity in submitting grant applications or getting contracts and material-transfer agreements through the university bureaucracy. Where faculty members could once pick up the phone and speak with a local grants administrator or human resources agent, now everything ran through computerized systems, making administrators largely unreachable—and accountable only to administrators above them, rather than to the faculty they ostensibly support.

Together we explored the public disinvestment in universities and its impact on finances, the changing composition of boards of trustees and members’ increasing tendency to impose their values, and the hermetic practices for recruiting and appointing senior administrators.

Despite our differences, we all shared one common experience: the disempowerment of faculty and deans at the expense of centralized administration. We also agreed, however, that the university had excelled in at least one area. “We have become a leader in corporate governance,” reported one faculty member with extensive administrative experience.

The Larger Promise of Budget Activism

As any reader of Academe knows, the consolidation of administrative power in the hands of people more versed in corporate law or business than in research or teaching is hardly unusual. Indeed, our experiences at Hopkins are probably normative across private research universities today. Public institutions have also thrown up formidable barriers to shared faculty governance as they hire more leaders from the worlds of business and finance.

It's precisely because our experience is broadly shared, however, that our pushback offers broader lessons. The most instructive message for us was this: budgetary issues could emerge as an effective tool for faculty mobilization.

Budget activism at JHU was not just learning about finances. It was also a means to share information about the university. It helped nurture the capacity of faculty to understand the institution, particularly its diverse teaching and research landscape, and to engage with it from a place of knowledge.

It is delusional to imagine that the administrative domains of finances and budgets can be divorced from faculty domains of teaching and research. Only by taking on a greater voice in the budgetary domain can faculty preserve the university’s essential mission. Only thus can we return to a place where budgets exist to support the university’s mission rather than to maintain credit ratings or university rankings and bragging rights in trustee meetings.

At Hopkins, the InterDiv Committee is now working to become an AAUP chapter. Drawing leadership from across the university’s varied divisions, we hope to offer a strong and robust voice and to partner with senior administrators for transparency and better decision-making. We’ve already been discussing the campaigns to come.

Our first goal is to encourage the university to comply with AAUP-supported standards on matters of governance. The joint Statement on Government, cited above, says that the allocation of resources is a responsibility shared by the governing board, the president and staff, and the faculty and that each should “have a voice in the determination of short- and long-range priorities.”

We will also push for a more formal faculty role in the selection of the president and other senior administrators, as other AAUP documents advise. Currently, senior administrators select faculty representatives for the search committees for other senior administrators. The AAUP is clear on this issue: faculty representatives should be elected by the faculty and not appointed by the administration.

In addition, we want the university periodically to undertake a transparent review of the performance of presidents and other senior administrators. Whatever review currently exists is performed exclusively by the board of trustees and behind closed doors, and the current president has twice been reappointed to new five-year terms long before his regular term expired. Although he has lost support of faculty across the university, perhaps a majority, he clearly retains the robust support of his board. The structural cleavages that result can only be bad for the institution.

Ultimately, we need to restore a system in which the university’s senior administrators feel accountable—not just to the board of trustees but also to other campus constituencies. Accountability from below is the means to better institutions and better governance. And it all starts with budgets.

François Furstenberg is professor of history at Johns Hopkins University. His email address is [email protected]. Naveeda Khan is associate professor of anthropology at Johns Hopkins. Her email address is [email protected]. They have helped to reorganize the JHU AAUP chapter.