- About

- Programs

- Issues

- Academic Freedom

- Political Attacks on Higher Education

- Resources on Collective Bargaining

- Shared Governance

- Campus Protests

- Faculty Compensation

- Racial Justice

- Diversity in Higher Ed

- Financial Crisis

- Privatization and OPMs

- Contingent Faculty Positions

- Tenure

- Workplace Issues

- Gender and Sexuality in Higher Ed

- Targeted Harassment

- Intellectual Property & Copyright

- Civility

- The Family and Medical Leave Act

- Pregnancy in the Academy

- Publications

- Data

- News

- Membership

- Chapters

Data Snapshot: Trends in Faculty Participation in Presidential Searches

AAUP governance surveys chart a century of growing faculty involvement.

A central concern of the AAUP since its founding in 1915 has been to advocate for meaningful faculty participation in institutional decision-making. The Association has not only issued policy statements on the proper conduct of academic governance but has also at various times conducted or sponsored national surveys to assess the prevalence of governance practices. One focus of these surveys—presidential searches—provides an opportunity to chart an area in which the work of the Association has resulted in lasting change, though those results have recently become contested.

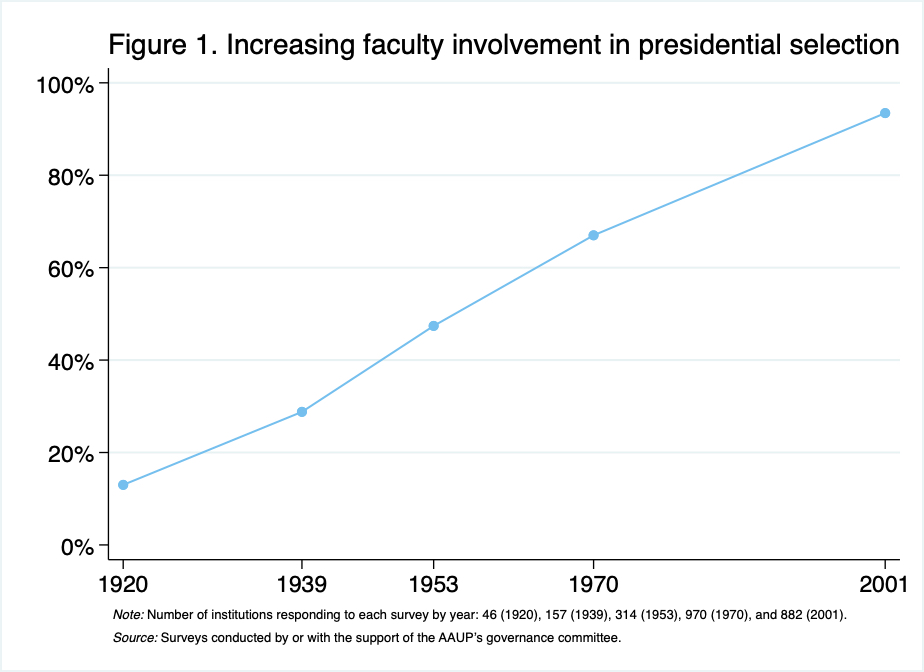

The AAUP’s governance committee conducted surveys in 1920, 1939, 1953, and 1970, and in 2001 it provided assistance to a doctoral student who conducted a survey on governance practices. Although the questions on these surveys changed over time, each survey contained a question that asked generally about faculty participation in presidential searches. Combined, the results of these five surveys provide an outline of a broad trend toward increasing faculty involvement in the selection of college and university presidents (see figure 1). By the 2001 survey, faculty participation in presidential searches had become the national norm.

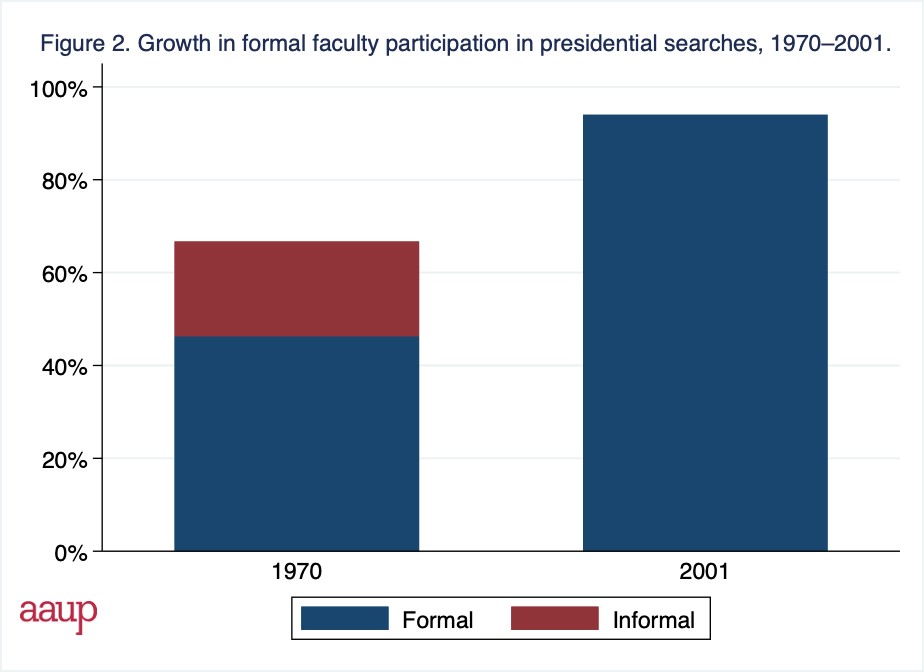

The 1970 survey provides an interesting opportunity for further analysis, because it inquired not only about whether faculty participated in institutional decision-making but also about their level of participation. On the basis of that analysis, the overall finding of increasing faculty participation by 1970 needs to be tempered by the finding that some 20 percent of responding institutions allowed only for informal participation in the selection of presidents, while 46 percent of responding institutions reported formal participation. In addition to the breakdown of the various levels of participation, the 1970 survey allows for a comparison of levels of decision-making among the various areas: on a list of thirty-one areas ranked by extent of faculty participation, presidential selection was twenty-fifth, just below the selection of deans and above decisions concerning the physical plant.

The absence of any governance surveys during the three decades between 1970 and 2001 presents some difficulty in charting the development of faculty participation in presidential searches during that period. The 2001 survey contained the rather specific question whether any faculty members had served on the most recent presidential search committee, which is clearly a formal means of faculty participation and which some 94 percent of responding institutions reported had occurred. Thus, over the course of those three decades, the rate of formal participation roughly doubled, and such participation had clearly become the norm throughout US higher education (see figure 2). Yet, the surveys mark only two points of that development.

Fortunately, 1991, Judith Block McLaughlin and David Riesman reported on a decade-long study of presidential searches that fills in part of the gap between those two governance surveys. Their report, published by the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching, provides a thorough account of the increasing participation of faculty representatives in presidential searches throughout the 1980s, which, by their account, was the time period in which current norms of faculty participation in presidential selection were set. They approached the subject through a series of qualitative case studies that provide deep insights into the discussions around confidentiality and openness of the presidential search process that accompanied the changes in presidential search practices that occurred during this time period—discussions that are highly relevant to concerns that are reemerging today.

One of the case studies that McLaughlin and Riesman considered, that of the pseudonymous “Abbott College,” begins with a vivid account of how presidential searches were commonly conducted in the 1950s, when fewer than half of the institutions surveyed by the AAUP reported any kind of faculty participation:

When the twelfth president of “Abbott College” was chosen, several influential members of the board of trustees discussed among themselves who would be well suited for the presidency. When they arrived at a name they found mutually agreeable, they approached this man one night as he was having dinner at one of New York’s more prestigious private clubs and offered him the position. Intrigued by the invitation, he was quickly persuaded to accept the presidency, and his appointment to the position was announced to the campus the next day.

By the mid-1980s, when the trustees began the selection of the fourteenth president, McLaughlin and Riesman reported,

They realized that all-trustee searches were an anachronism at Abbott College, as at practically every other college or university on the landscape of American higher education. The faculty would have to be involved in some manner if the search were to be seen as legitimate. After consulting with leaders of the faculty, the Abbott College trustees assembled a fourteen-member search committee which included seven trustees, five faculty members chosen by the faculty, and two students chosen by the student government. No longer was the determination of the presidency to be made over dinner at an all-male New York club.

The increasing participation of faculty and other constituents in the selection of presidents brought with it questions about confidentiality and openness that would not have occurred at times during which a small group of trustees made that decision on their own. At the same time, McLaughlin and Riesman’s study documents the increasing use of search consultants. It is therefore not surprising that the AAUP’s governance committee addressed the issues posed by the use of search consultants, in particular with respect to confidentiality and openness, in the late 1990s. Its report cautioned,

The professional recruiter can help streamline the process, but members of the faculty must insist on the inclusiveness of the endeavor, even at the expense of efficiency, in order to ensure a salutary outcome. This means working for strong faculty representation on either a joint faculty/trustee committee that both identifies and narrows down the pool of candidates or, alternatively and less desirably, on a separate faculty committee with a more restricted charge. This representation should consist of individuals who have been designated by the faculty to solicit opinions from the faculty as a whole, thereby broadening the mandate for the candidate who is ultimately selected to become president of the institution. However the search is conducted, the names of finalists who visit the campus should be made known to the faculty as well as to other institutional constituencies, who should be provided with an opportunity to interact with them and furnish recommendations about their candidacies.

The above represents a summary of the AAUP’s position on presidential searches to this day.

While the overall development over the course of the last century has been one of increasing faculty participation, issues concerning the form of that participation have arisen in recent years. What was clearly the consensus in higher education some twenty years ago is being called into question, for instance, by the decision of the University of Wisconsin board of regents not to include faculty representatives on its most recent presidential search committee. Search consultants are citing “increasing trends” toward confidentiality for which there is, at best, anecdotal evidence, but which are difficult to refute in the absence of any subsequent governance survey since 2001. It will require vigilance and activism to ensure that faculty participation in presidential selection is maintained at the level that it has throughout the recent past.

Further Reading

“Final Report on the 1953 Study.” Bulletin of the American Association of University Professors 41, no. 1 (Spring 1955): 62–81.

Kaplan, Gabriel E. “Preliminary Results from the 2001 Survey on Higher Education Governance.” https://www.aaup.org/NR/rdonlyres/449D4003-EB51-4B8D-9829-0427751FEFE4/0/01Results.pdf.

McLaughlin, Judith Block, and David Riesman. Choosing a College President: Opportunities and Constraints. Princeton, NJ: Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching, 1991.

“On the Use of Executive Recruiters in Presidential Searches.” Academe 83, no. 5 (September–October 1997): 82–3.

“Report of Committee T on Place and Function of Faculties in University Government and Administration.” Bulletin of the American Association of University Professors 6, no. 3 (March 1920): 17–47.

Hans-Joerg Tiede is a senior program officer and researcher at the AAUP. His email address is [email protected].