- About

- Programs

- Issues

- Academic Freedom

- Political Attacks on Higher Education

- Resources on Collective Bargaining

- Shared Governance

- Campus Protests

- Faculty Compensation

- Racial Justice

- Diversity in Higher Ed

- Financial Crisis

- Privatization and OPMs

- Contingent Faculty Positions

- Tenure

- Workplace Issues

- Gender and Sexuality in Higher Ed

- Targeted Harassment

- Intellectual Property & Copyright

- Civility

- The Family and Medical Leave Act

- Pregnancy in the Academy

- Publications

- Data

- News

- Membership

- Chapters

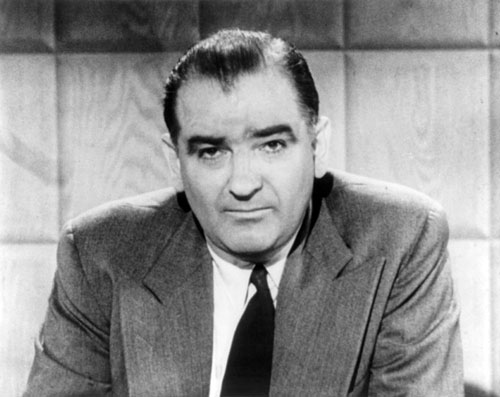

Exhuming McCarthy (Meet Me at the Book Burning)

Faculty members respond to the Professor Watchlist

As the AAUP recently noted in its statement Targeted Online Harassment of Faculty, current efforts by private groups to monitor faculty conduct are raising academic freedom concerns. Almost fifteen years ago, an AAUP committee noted that such groups, “parading under the banner of patriotism or acting to further a specific cause, have been monitoring academic activities and have denounced professorial departures from what these groups view as acceptable.” The committee singled out Campus Watch for its attacks on professors of Middle Eastern studies and found precursors in the 1960s activities of the John Birch Society and in the 1980s efforts of the Accuracy in Academia movement.

The Association rebuked the John Birch Society in 1962, Accuracy in Academia in 1985, and Campus Watch in 2002, condemning their activities, respectively, as “the very antithesis of the scholarly community”; the antithesis of “the freedom of faculty members to teach and of students to learn, as well as a threat to the freedom of the academic institutions themselves”; and “a menace to academic freedom.” But the antecedents of such groups—and the AAUP’s involvement with them—date back even further. In 1924 the AAUP investigated the case of a faculty member at the University of Montana who was suspended through the end of his contract because the American Legion claimed he had failed to support US efforts in World War I.

In addition to calling for the dismissal of individual faculty members, US anti-Communist movements have a long tradition of maintaining blacklists, with the McCarthy-era Hollywood blacklist being perhaps the most famous example. Predating this blacklist by more than a decade was conservative political activist Elizabeth Dilling’s 1934 book, The Red Network—A Who’s Who and Handbook of Radicalism for Patriots. It enumerated more than 460 “radical” organizations and some 1,300 individuals who were their members or sympathizers. Among the organizations listed were the American Federation of Teachers (AFT) and the American Civil Liberties Union. The latter commented in a pamphlet that the book, “despite its absurdity in including as reds such persons as Mrs. Eleanor Roosevelt, Mayor LaGuardia, Mahatma Gandhi, and [British prime minister] Ramsay McDonald, is taken seriously by the hundreds of sheriffs and chiefs of police to whom it evidently has been sent. All the present and former officers and committeemen of the Civil Liberties Union are of course included.” Regarding the AFT, Dilling notes: “Radical; stands for abolition of R.O.T.C.; recognition of Russia; full ‘academic freedom’ to teach anything, including Socialism, Communism, or Atheism.”

Among the individuals Dilling listed were the three professors who in 1936 constituted the AAUP’s Committee B on Freedom of Speech: AAUP founder Arthur O. Lovejoy, Harvard law professor and free speech scholar Zechariah Chafee, and University of Chicago physiology professor and AAUP president Anton Julius Carlson. The Association created the committee to cooperate with other national organizations and counter attacks on free speech that originated outside of academia, in contrast to Committee A on Academic Freedom and Tenure, which focused on abridgment of academic freedom by administrations or boards of trustees.

In many cases, including ones today, controversies over faculty activities have led to threats of physical violence against individual faculty members or the institution—threats that have included, in the case of women faculty, sexual assault. When Indiana State University professor Scott Chisholm burned a US flag in his classroom in 1967, the Terre Haute city council, the American Legion, and other groups demanded his dismissal, and a member of Congress called for his deportation to Canada. Chisholm received anonymous threatening phone calls, and the administration suspended him because of concerns for “his safety in view of the highly emotional and inflammatory reactions which [the administration] thought likely to follow and which did occur.” As a publication by Phi Delta Kappa, a professional organization for educators, observed, “at no time during these weeks of flag waving did the ISU administration make any apparent effort publicly to defend academic freedom.” Almost four decades later, the University of Southern Florida suspended Professor Sami A. Al-Arian after a controversial interview on the O’Reilly Factor some two weeks after the attacks of September 11, 2001. As an AAUP investigating committee subsequently observed, the focus of that interview was his “association with people revealed to be terrorists and inflammatory remarks he had made about Israel over a decade earlier,” and its broadcast was followed by threats that caused the university to evacuate the academic building in which Professor Al-Arian worked and to suspend him “to ensure safety.”

Today’s iterations of the faculty blacklist are websites such as Campus Reform, College Fix, or Professor Watchlist. The stated mission of Professor Watchlist, which is funded by the right-wing advocacy group Turning Point USA, is “to expose and document college professors who discriminate against conservative students and advance leftist propaganda in the classroom.” An earlier version of the mission statement, subsequently modified, included the promotion of “anti-American values” as among the reasons for inclusion on the Professor Watchlist, which at least seemed like an honest statement of allegiance to the McCarthyist tradition. It should go without saying that AAUP-supported principles of academic freedom do not protect propagandizing in the classroom or discriminatory treatment of students because of their political beliefs. However, the Association has long held that where questions arise concerning the propriety of conduct of a faculty member, the matter should be referred to appropriate faculty bodies at the faculty member’s institution. Furthermore, there is a notable discrepancy between the stated purpose to list professors because of their classroom conduct and the actual practices of Professor Watchlist: a statistical analysis of the cases reported on Professor Watchlist by Marion Leary, published on the Huffington Post, found that barely more than half involved classroom conduct of faculty members.

Attempts to silence faculty members have a long history, and the AAUP has long sought to counter them. In 1915, the AAUP’s founding year, the Association’s leaders observed that the social sciences in particular faced a “danger of restrictions upon the expression of opinions which point toward extensive social innovations, or call in question the moral legitimacy or social expediency of economic conditions or commercial practices in which large vested interests are involved.” There is no reason to believe that the situation today is significantly different.

It is the responsibility of the academic community to counter attempts to silence faculty members. Administrations, governing boards, and faculties, individually and collectively, need to speak out clearly and forcefully to defend academic freedom and to condemn targeted harassment and intimidation of faculty members. When administrations or boards fail to do so, the faculty needs to act collectively. The recent case of Johnny Williams, a professor at Trinity College in Connecticut, has demonstrated that an AAUP chapter, faculty committees, and the faculty at large can succeed in opposing administrative overreach and defending the academic freedom of a colleague by standing together. As AAUP founder John Dewey observed in 1935, “If teachers do not stand fighting in the front rank for freedom of intelligence, the cause of the latter is well-nigh hopeless, and we are in for that period of intimidation, oppression, and suppression that goes, and goes rightly, by the name of Fascism and Nazi-ism.”

What follows is a selection of comments by professors who have found themselves on the Professor Watchlist.

Joe Kuilema, professor of social work at Calvin College: I’m actually very invested in dialogue between people who disagree, and in that way inclusion on this list is not at all reflective of who I consider myself to be or reflective of what my students have experienced in my courses. Certainly I have beliefs and truths that I hold dear, but I always want to make space for the perspectives of others and encourage my students to have authentically open minds about ideas that they may deeply disagree with. (Calvin College Chimes, December 2, 2016)

George Yancy, professor of philosophy at Emory University: If we are not careful, a watchlist like this can have the impact of the philosopher Jeremy Bentham’s Panopticon—a theoretical prison designed to create a form of self-censorship among those imprisoned. The list is not simply designed to get others to spy on us, to out us, but to install forms of psychological self-policing to eliminate thoughts, pedagogical approaches and theoretical orientations that it defines as subversive. (New York Times, November 30, 2016)

Beth L. Lueck, professor of English at the University of Wisconsin–Whitewater: With the dubious distinction of being one of the first professors to be named to the Professor Watchlist, there I was again—with my name and e-mail address in the public eye, a brief description of my crime (no more factual than its initial appearance online . . .), and an invitation to students to come after me (with a picture so I could be readily identified on campus). The online story in Slate was accompanied by an illustration of a professor with a target on his back. Given that the Wisconsin state legislature—now even more heavily Republican—is trying to pass a law permitting guns in the classroom on UW campuses, this is all too frightening. . . .

As a new administration takes over in Washington, DC, one that has been openly hostile to the professoriate, faculty at colleges and universities need to stand together. . . . We need to keep our message to students, to fellow faculty, to administration, and to the public consistent and strong. Education is about learning; it’s about being exposed to new ideas; it’s about debating openly and without fear. (Academe Blog, January 13, 2017)

Tobin Miller Shearer, professor of history at the University of Montana: Ever since I was watchlisted, I have been inundated with expressions of support from throughout Montana, across the country and around the world. If someone from Turning Point has the courage and integrity to meet with me, they have to know ahead of time that this community of friends, colleagues, family members and former students has got my back. They will be with me in spirit in the room. Hundreds of them.

There is Ray, whom I work out with in the gym, who came up to me and said, “Tobin, where do I have to stand? I’ll get in the way if they come to get you.” Ray is a veteran and a very big man.

There is Todd, a former student, who wrote, “Whatever the amount of insecurity and hatred that may exist, or try to manifest, there is 10 fold the amount of support, care, protection and love for you. . . . I am on your side!”

There is Valerie, another former student, who wrote, “I am just one who hopes that someday I too can be placed on a watchlist for dissident ideas, thoughts, and language. If I am ever lucky enough to make such a list, know that it was your classroom that gave me the voice I needed to resist the racist, misogynistic, and hate-filled discourse of our society. . . .”

So in this particular moment in history I will bring all the good humor, joy, subversiveness and academic rigor I can to the classroom. I will show up. I will stay engaged. And, as I posted on my door after Donald Trump was elected and my students of color witnessed a substantive rise in racial harassment right here in Missoula, my office will be a place where my students are cherished, where they will be as safe as my body and voice can make them, where they will be known by their names regardless of their identity. (Missoula Independent, December 15, 2016)

Charles Strozier, professor of history at the John Jay College of Criminal Justice, City University of New York: The profile of me on the Watchlist only mentions my work on global warming and terrorism. It seems to drive them to distraction that I would raise serious questions about global warming in the classroom and relate it to some of the most extreme forms of terrorism in the world.

But this is exactly what we mean by critical thinking. That critical thinking would come under such an assault is worrisome.

I tend to mock the Watchlist and all those who want to stifle intelligent inquiry. But I recognize I am also secure as a senior professor in a liberal city and a very good college. I worry about younger colleagues in those red states, and my contingent colleagues all over the country. They need to watch their backs — and we need to help them do it. That is why all of us need to speak out resoundingly against the Professor Watchlist. (Medium, December 14, 2016)

Anthea Butler, professor of religious studies at the University of Pennsylvania: Many professors and university officials do not know that these organizations, populated by their own students, exist. They are left flatfooted when lists like the Professor Watchlist appear. . . .

For tenured professors like myself, the Professor Watchlist is an annoyance that takes away from research, teaching and time with students. For professors on the tenure track, or lecturers who are trying to keep a contract job, being named on the Professor Watchlist could mean diminished opportunities for their careers if colleges and universities do not understand the purpose and nature of these groups.

These types of attempts to influence campus culture and teaching are disturbing. [They] create an environment where the very idea and understanding of academic freedom and first amendment rights are called into question—not only by students, but also by well-funded outsiders with agendas. (Guardian, December 2, 2016)

Matthew Boedy, professor of English at the University of North Georgia: Being a professor may be the only response we have in this age of institutional realignment and political headwinds too strong for critical thought. It may be the only route we have to a future. I don’t mean to sound frightened, but I am. But I am not worried about a watchlist; I am worried about what is to come.

And let me remind you that the best place we can be professors is the classroom. As it has always been. We can organize nationally and practice citizenship at the state level. But an impact we always have had is in the people sitting in front of us. Who call us professors.

If professors being professors is the effect of the Professor Watchlist, I say amen. (Academe Blog, February 8, 2017)

Robert Jensen, professor of journalism at the University of Texas at Austin: From a “critique” of my work on the latest Professor Watchlist, I learned that I’m a threat to my students for contending that we won’t end men’s violence against women “if we do not address the toxic notions about masculinity in patriarchy . . . rooted in control, conquest, aggression.”

That quote is supposedly “evidence” for why I am one of those college professors who, according to the watchlist’s mission statement, “discriminate against conservative students, promote anti-American values and advance leftist propaganda in the classroom.” Perhaps such a claim could be taken more seriously were it not coming from a project of conservative nonprofit Turning Point USA, which has its own political agenda—namely educating students “about the importance of fiscal responsibility, free markets and limited government. . . .”

It would be easier to dismiss this rather silly project if the U.S. had not just elected a president who shouts over attempts at rational discourse and reactionary majorities in both houses of Congress. I’m a tenured full professor (and white, male, and a U.S. citizen by birth) and am not worried. But, even though the group behind the watchlist has no formal power over me or my university, the attempt at bullying professors—no matter how weakly supported— may well inhibit professors without my security and privilege.

If the folks who compiled the watchlist had presented any evidence that I was teaching irresponsibly, I would take the challenge seriously. At least in my case, the watchlist didn’t. But rather than assign a failing grade, I’ll be charitable and give the project an incomplete, with an opportunity to turn in better work in the future. (Dallas News, November 30, 2016)

Hans-Joerg Tiede is a senior program officer in the AAUP’s Department of Academic Freedom, Tenure, and Governance.

Photo courtesy of the Library of Congress.