- About

- Programs

- Issues

- Academic Freedom

- Political Attacks on Higher Education

- Resources on Collective Bargaining

- Shared Governance

- Campus Protests

- Faculty Compensation

- Racial Justice

- Diversity in Higher Ed

- Financial Crisis

- Privatization and OPMs

- Contingent Faculty Positions

- Tenure

- Workplace Issues

- Gender and Sexuality in Higher Ed

- Targeted Harassment

- Intellectual Property & Copyright

- Civility

- The Family and Medical Leave Act

- Pregnancy in the Academy

- Publications

- Data

- News

- Membership

- Chapters

Civility, Academic Freedom, and the Neoliberal University

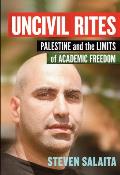

Uncivil Rites: Palestine and the Limits of Academic Freedom by Steven Salaita. Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2015.

Deploying language that undermines the commonplaces of respectable speech threatens the authority of the elite, who have the power to name as “civil” and “uncivil” those elements of our rhetoric that impose meaning (or cliché) on the various struggles of the world. Academic freedom is often a disturbance. It does not yet fully accommodate dissent. —Steven Salaita

On September 11, 2014, the verdict was read. Steven Salaita, a Palestinian American professor who had been offered a tenured position in the American Indian Studies Program at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, had been “unhired.” The New York Times ran an article the next day with the headline, “Professor’s Angry Tweets on Gaza Cost Him a Job.” In Salaita’s own words, “contrary to the University’s expectations, the firing made me something of a free speech darling (or the world’s most violent person since Stalin).”

Part memoir, part reportage, and part analysis, Uncivil Rites: Palestine and the Limits of Academic Freedom documents the personal, political, philosophical, and intellectual stakes of working in a profession where free speech is under attack in the name of protecting the code of civility. But what is civility? Whom does it protect or destroy? Who determines what is civil or uncivil? While these stakes form the fundamental framework for Salaita’s argument, they are not limited to the issues surrounding civility. In fact, the book can also be read as an argument for the importance of “uncivil” discourse in the fight for justice, liberation, and freedom from corporate, imperial, and colonial control and oppression. After all, as Salaita points out, “in colonial landscapes, civility is inherently violent. You simply have to learn to discuss violence the right way.”

Uncivil Rites is a book not just about Steven Salaita, or his tweets, but also one about the lies and the truths we hide in academia: lies about universities and their increasing dependence on outside donors who dictate who is hired, who is fired, what is taught, and what cannot be said or taught; lies about how ethnic, sexual, and cultural minorities are actually treated, as opposed to how they are portrayed in their institutions’ multicultural and diversity initiatives; and lies about how discourse that exposes the nature of the plight of the Palestinians and the Israel-Palestine conflict is suppressed, vilified, or labeled “anti-Semitic.” Salaita is astute in pointing out that the experiences of those who support Palestinian human rights today parallel those of many Jewish students and faculty members, who “were long marginalized in the academy because of their supposed dangers to Anglo civility.”

Salaita is careful not to reduce identity politics to essentialism, instead allowing the reader to witness his own complex position within the academy and within the larger society. In one of the book’s twenty-three essays, “On Being Palestinian and Other Things,” Salaita examines the hybrid nature of his own ethnic identity: his father has Jordanian-Palestinian heritage, his mother was born and raised in Nicaragua but strongly identifies with her Arab roots, and he himself grew up in Appalachia. Rather than celebrate the virtues of the postmodern hybrid identity that makes him the quintessential “displaced subject,” he makes the point that such multiple affiliations have provided a lack of rooted dogmatism, patriotism, or “ethnonationalism.” It is here that the book makes a shift from an analytical discussion of the role of the corporate and imperial university to a personal discussion of the ethics, or the efficacy, of lying, and then of the gradual uncovering of the truth.

In a chapter that shares the book’s title, Salaita begins by stating, “Lying to children is not merely convenient; it is often ethical.” Yet the timing of such “ethical” lying matters. Salaita gives as an example an exchange he had with his young son just after receiving a letter from Phyllis M. Wise, UIUC’s then chancellor, informing him that her administration would not be submitting to the board of trustees a recommendation that he be appointed to the UIUC faculty in September and explaining that “we believe that an affirmative Board vote approving your appointment is unlikely.” As he read the letter in utter disbelief, Salaita turned to his wife Diane for an explanation:

“Have I been fired?”

“Yes.” She was unequivocal.

“What the fuck?” I covered my face with both hands. I was immediately inflicted by a feeling of shame.

At this precise moment, his young son, noticing his father’s distressed look, asked, “Okay, Papa?” “Yes my love,” replied Salaita. “Papa’s okay.” Yet, Salaita’s detailed and emotional narrative makes it amply clear that he was not okay. Who would be? What could he have told his young son at that moment other than a lie to cover up his own emotional state? Here, lying is not just convenient but also protective.

This brief letter from Chancellor Wise, as the book recounts, would be the beginning of a series of “uncivil rites” causing a systematic destruction of Salaita’s academic career as well as the psychological and economic health of his family. It marked the beginning of a long legal battle to establish the value of academic freedom and free speech as well as the triggering event for an AAUP investigation into Salaita’s dismissal from a tenured faculty position on the grounds of his “uncivil” tweets. While Salaita has had to bear the burden of his abrupt termination, his case has become a landmark in exposing a broken system of shared governance and violations of the principles of academic freedom and tenure.

It is easy to focus on the book as a case study of violations of academic freedom. Salaita notes that his case is not an exception. The neoliberal university has never been open to the kind of free speech that openly critiques the failure to provide a democratic and accessible education for everyone. He maintains that the very notion of academic freedom for all ought to be contested: “We ought to complicate academic freedom even as we vigorously defend it.”

Chapter 16, “The Chief Features of Civility,” is the only chapter that provides an image, preceded by a caption: “Here is what civility looks like at the University of Illinois.” The image is of Chief Illiniwek, “the official university mascot who was forcibly ‘retired’ in 2007 because of the threat of NCAA sanction.” In fact, if Uncivil Rites can be read as a political memoir, this chapter is where the book is most powerful: “The chief, despite his ostensible retirement, is central to notions of civility and practices of diversity at UIUC. He is also partly responsible for my termination.” It is also here that Salaita reveals how his colleagues in the American Indian Studies Program have not only suffered “the indignities of the immoral mascot, but an onslaught of racism from his obsessive supporters.” The discussion of the “chief” as the mascot lays bare the relationship between civility and racism. The inauthentic chief not only stands as a visible symbol of a history of colonization and racism on the UIUC campus but also propels the unacceptable forms of institutional racism “under Chancellor Wise’s watch.” In a corporatized university, the chief is a brand, “an investment in consumer culture. . . . It produces loyalty, which in turn produces the sort of nostalgia that generates attachment and its desirable byproduct, alumni giving. The chief is a merchandised identity.”

In the end, the book is not just about Palestine and the limits of academic freedom but also about a clarification––a clarification of the relationship between “civility” and academic freedom. The code of civility, according to Salaita, is used to punish those who critique the power apparatus, to disempower faculty and students who speak up against the constant erosion of their rights and democratic ideals and demand the social and racial justice that a multicultural mission aims to foster. To raise these issues of justice forcefully and clearly and call for an end to forms of dehumanization (whether in Palestine or within the classroom and the university) is marked as “uncivil.”

Uncivil Rites is an unusual book, written at an unusual time in an age marked more by conflicts than by resolutions, when academic freedom and tenure are under attack and the easy acceptance of codes of civility dictated by administrations threaten intellectual freedom in many American institutions. This book serves warning to all of us: using civility as a mechanism for suppressing forms of truth or ideological opposition will ultimately cause the demise of our profession and of the institutions of higher learning that house us.

Reshmi Dutt-Ballerstadt is professor of English and coordinates the Gender Studies Program at Linfield College. She is the author of The Postcolonial Citizen: The Intellectual Migrant. Her e-mail address is [email protected].