Discussions regarding the personal finances of adjunct faculty members do not typically include retirement saving. After all, low pay levels would seem to make saving for retirement difficult or even impossible for many adjunct faculty. According to the TIAA Institute’s 2018 Adjunct Faculty Survey, adjunct faculty—defined in the survey as part-time non-tenure-track faculty members who do not hold career employment outside of higher education and who are not retired from a tenured faculty position—were paid an average of only $3,000 per course, and almost 60 percent reported receiving less than that. Nonetheless, 64 percent of the 502 survey respondents drawn from a Research Now online research panel reported that they had personally saved for retirement in the prior year. (Responses were weighted by age, gender, and highest degree attained.)

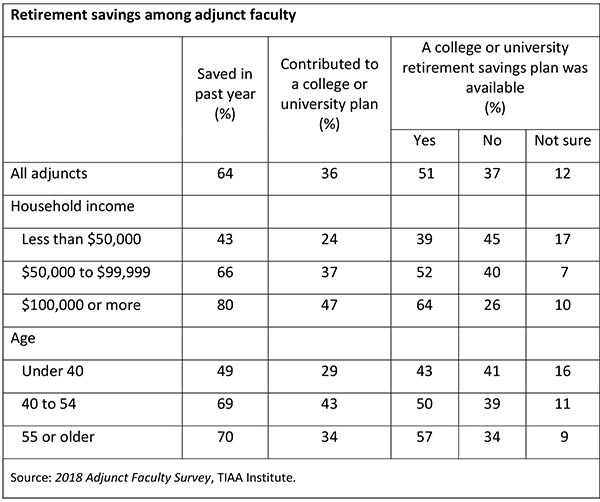

Reconciling this seeming paradox begins with recognizing that financial decisions are made in a household context. One-third of adjunct faculty are in households with incomes under $50,000, and among this group, just 43 percent reported saving for retirement during the past year. In households with higher incomes—where adjunct faculty earnings are not the primary income source—rates of retirement savings are much higher. For example, 80 percent of those with household income of $100,000 or more reported saving for retirement. This suggests that the capacity of adjunct faculty to prepare for retirement depends to a large extent on the earnings of other household members. Rates of retirement savings are also affected by the fact that most adjuncts are at an age where planning for retirement becomes a focus. The average age among adjunct faculty is fifty; 72 percent are age forty or older.

Overall, 36 percent of adjunct faculty reported contributing to a college or university retirement plan. As expected, adjunct faculty with higher household incomes were more likely to have contributed to such a plan.

Fifty-one percent of adjunct faculty reported that a retirement savings plan was available to them at a college or university where they worked, 37 percent reported that a plan was not available, and 12 percent were not sure whether a plan was available. This implies a participation rate among those offered a plan in the 55 to 70 percent range.

Among adjunct faculty who did not personally save for retirement in the prior year, 74 percent either had no plan available from a college or university or were not sure whether a plan was available. Somewhat surprisingly, adjuncts with higher household incomes more often reported that a retirement savings plan was available to them at a college or university where they worked. Similarly, older adjuncts more often reported access to a college or university plan. Because there is no reason to expect plan availability to be correlated with age or household income, this finding implies that subgroups of adjunct faculty—in particular, those who are younger and have lower household incomes—are unaware in some instances that a retirement savings plan is available to them. The survey did not ask adjunct faculty about employer matching contributions in their retirement plans.

The survey’s findings also provide a broader perspective on adjunct faculty finances beyond just saving for retirement. Three-quarters of adjunct faculty households are carrying debt. The most common debt sources are credit cards and home mortgages. Not surprisingly, student loan debt is common among younger adjuncts—48 percent of those under age forty carry such debt, as opposed to 12 percent of those age fifty-five and older.

Paul Yakoboski is a senior economist at the TIAA Institute.