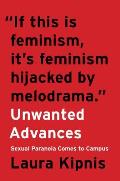

Unwanted Advances: Sexual Paranoia Comes to Campus by Laura Kipnis. New York: HarperCollins, 2017.

Laura Kipnis’s new book joins a groundswell of critical commentary—including the AAUP’s 2016 report The History, Uses, and Abuses of Title IX—on how Title IX investigations involving sexual assault and harassment are conducted at universities and colleges across the nation. Unwanted Advances recounts how, in the name of feminism, recent changes in the administration of Title IX have upended sex on campus, muddying what constitutes sexual behavior, acceptable or otherwise. All the while, confidentiality and privacy concerns cloak these developments, frustrating, as the book shows, any clear-eyed assessment of their impact.

Kipnis is well positioned to evaluate the Title IX investigatory process, having famously faced her own Title IX complaint after publishing a 2015 essay in the Chronicle of Higher Education. The subsequent story of how the publication came to be construed as a potential case of sex discrimination, and the bureaucratic convolutions of the resulting investigation, open quickly into more general commentary on the stifling effects of contemporary Title IX enforcement on academic freedom and campus sexual cultures. Kipnis presents her own encounters as indicative of a trend across college campuses, one where expansive narratives of gendered sexual vulnerability have collided with demands for institutional responsibility in unsettling and unprincipled ways.

Unwanted Advances is a much-needed attempt to rein in efforts to combat collegiate sexual harassment and assault that would sacrifice clear process and fail to safeguard the rights of the accused. The book is at its strongest when it documents the overreach and “procedural haphazardness” of contemporary Title IX investigations, which include the refusal to provide those accused with any charges. Kipnis recounts her inability to secure the charges against her in writing—her Title IX investigators insisted on enumerating them over a Skype interview that she was forbidden to record. Others report arriving at their hearings still in the dark, knowing neither the scope nor the specifics of the accusations against them. Kipnis conveys with blunt humor the confusion and dread that accompany intense scrutiny and amorphous process. The new approach, she writes, “has been disastrous for anyone who cares about either education or democracy, beginning with the manner in which these guidelines were implemented: with a tire iron.”

The brashness that makes the book an engaging read can, however, cut the other way when snark presents as gospel. When a student tells a friend the morning after a sexual encounter that she has “no memory” of the events of the previous evening and then, three months later, files a complaint, Kipnis disparages the student for her “miraculous” memory “recovery”—an assessment the reader is meant to take on faith. The most generous reading would view this particular characterization and others like it as part of a larger criticism of the procedural insufficiencies that accompany many current Title IX investigations. Given the prior accounts of disastrously opaque Title IX investigative procedures, it may be tempting to leave it at that.

But if Title IX investigations have turned, as Kipnis suggests, the old “he said/she said” into “she said/ let’s get him,” a counter of “she’s wrong” is hardly a more feminist approach. To say so is not to indict or disavow Kipnis’s account of the interpretive excesses and procedural insufficiencies that can plague current Title IX investigations. It only affirms that we need more complex reckonings of how sex and legal or administrative attempts to govern it might work or fail to work. This is the point, after all, of the book, and that point is well taken—if not always by Kipnis herself.

When, for instance, Kipnis uses language that imputes without naming the fraught and public saga of the relationship between sex, memory, trauma, and public accountability, she sidelines a rich set of social, academic, and activist relationships and debates. This lack of engagement—particularly, as queer studies scholar Lisa Duggan has written, with feminist, queer, and race-conscious activism and academic work—matters. It matters because Kipnis is writing, ultimately, about what counts as reasonable behavior, and understanding of what counts is always shot through with corresponding expectations about gender, race, class, disability, and so forth—an insight advanced by feminist activists, theorists, and legal scholars, queer scholars, and people of color, including those instrumental in the development of sex discrimination as a necessary, groundbreaking legal and political concept. (It is not difficult to imagine a scenario where a violation might go unreported as a result of shame or unfamiliarity with institutional process, or because of historically grounded suspicion or fear of the very institutions that are supposed to offer relief.)

Sidestepping that body of work allows Kipnis to offer this retrograde stunner of a “reality check”: “single non-hideous men with good jobs . . . don’t have to work that hard to get women to go to bed with them in our century.” It allows her to embrace the right-wing rejection of a cartoonish notion of social identity’s relationship to politics—“despite being a certified left-wing feminist, I just don’t believe that experience or identity credentialize you intellectually”—while at the same time relying on gendered and classed tropes to make her case (God bless those single, nonhideous men with good jobs, invariably keeping their hands to themselves).

While Kipnis rightly rails against empowering the university to administer the sexual lives of its students and employees, the central problem remains one of how women and men relate to each other on campus. Her solution: fight heterocompliance in women. Teach women how to say no, how to fight, and let them know that they have to protect themselves (say no again—this time to any alcohol on offer). Refuse and defy; however, do little to upend the overarching narrative of Title IX. Sidelining recent feminist and queer race-conscious history and research lets Kipnis simply flip the script to emphasize the vulnerability of the accused and the complicity of the women (always women) who do the accusing in their own victimization.

But while the narrative of young women in danger oils the Title IX machine, what’s happening on campus is feminism hijacked by something more than, as the book cover puts it, “melodrama.” Kipnis gives us a few hints of what that something might be: a mention of carceral feminism (or “the hawkish, security state swerve in social policy on women’s issues”), the creation of a sexual safety industry, the incursion of corporate management practices into faculty-university relations, and the rise of student debt and the student-customer-consumer model of education delivery. Here, Kipnis gestures toward other dimensions of the resurgent prohibition of campus intergenerational sex and a campus sexual culture premised on gendered sexual fragility— dimensions that other work in the field, like Jennifer Doyle’s Campus Sex, Campus Security, take on. For Doyle, campus sexual politics are about an imagined and real population of women (“the very young girls,” as she provocatively names them), those who are able to go to college, who must be kept safe and sexually protected, and in whose name the securitization of campus—the armed campus cops, the racial and class profiling of those who don’t seem to belong—is further justified and entrenched.

Understanding campus sexual norms and policies as a part of broader security cultures and the business of the university itself crucially reframes the question of what to do about sexual assault and harassment on campus. Doyle’s account positions us to ask questions about sex, desire, reasonableness, and believability that aren’t automatically parsed from larger social realities on and off campus, where feminists already organize as a part of Black Lives Matter, Students for Justice in Palestine, blockades against deportations and imprisonment, and campaigns for gender-neutral bathrooms. Situating the current interpretation of Title IX within these contexts could move us beyond Kipnis’s simple diagnosis of “the reigning student versions of feminism” as “a mess” and toward the kinds of connections and solidarities that would allow for a reenvisioning not only of what popularly counts as feminist activity but also of the political economy of the campus itself and how activism fits within it.

In this way we might take Kipnis’s crucial criticism of Title IX’s current application to insist on a comprehensive accounting of how universities conduct investigations as well as a more robust, integrated vision of sex discrimination on campus. Congress itself passed Title IX to secure a range of educational opportunities for women, including access to higher education, athletics, career training and education, education for pregnant and parenting students, employment, the learning environment, math and science education, standardized testing, and technology. To emphasize this does not diminish instances of sexual violation, but it also does not install them—stripped of any thorough accounting of race, ability, gender identity, class, or citizenship status—as the premier feminist issue on or off campus. Doing so could bring us much closer to what Unwanted Advances seeks: an end to the “historical amnesia” that facilitates the “purification” of college campuses at the expense of basic guarantees of academic and other kinds of freedom.

Rana Jaleel is assistant professor of gender, sexuality, and women’s studies at the University of California, Davis, and a member of the AAUP’s Committee on Women in the Academic Profession. Her email address is [email protected].