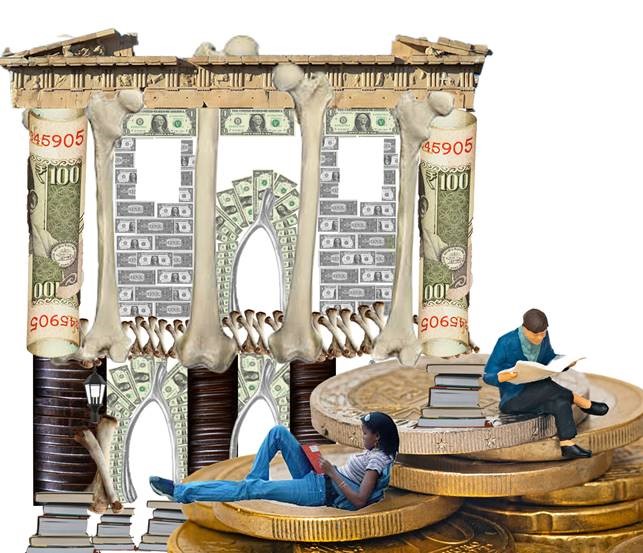

Art Credit: Maria Schirmer Devitt, U of D: University of Debt, 2021, digital collage.

Of all the ills plaguing higher education in the United States during the COVID-19 pandemic, perhaps none has received as much public attention, at least recently, as the student debt crisis. Today it is practically common knowledge that more than forty-five million Americans owe in excess of $1.7 trillion. Yet for all the growing public awareness of the crushing loads of student debt, there is surprisingly scant discussion about the educational effects of debt on students’ learning experiences.

Here I argue that debt produces what philosopher John Dewey called “miseducative” experiences. I agree with those like the Debt Collective (of which I am part) who contend that debt cancellation should be universal for economic, political, and ethical reasons. Concluding that debt is detrimental to educational experience, I add an educational reason for debt abolition to ongoing debates on the subject. Taking steps to overcome the adverse impact of debt on educational experiences present and future by eliminating all current debt, and by funding free public higher education, is sound pedagogically. Furthermore, full cancellation of student debts accrued in the past serves as a reparative policy that addresses educational harms done to those students, especially BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, and people of color) students, who had to take on debt to have an opportunity to access higher education.

The Debt Crisis

The student debt crisis, as economist Marshall Steinbaum succinctly puts it, can be traced to three intersecting phenomena. “First, public funding for higher education has been slashed, shifting nearly every institution toward a tuition-based business model,” he argues. “Second, that trend has been supported by a relatively open-handed federal policy when it comes to originating loans.” This second point deserves a brief explanation. Steinbaum writes, “The federal view is that more people should be able to pursue more higher education whatever the tuition. Hence loan limits have increased, and federal student loans come with more favorable terms than most unsecured debt.” In effect, this amounts to a federal bailout program for states that have cut funding to higher education. Unfortunately, the bailout is borne on the backs of students who will carry debt for an extended period due to a precarious labor market. Finally, Steinbaum writes, “More people want to attend college thanks to the raising of credential requirements for any given job or salary, what scholars have come to call ‘credentialization.’”

The 2008 financial recession and now the COVID-19 pandemic have exacerbated a preexisting condition in higher education: underfunded public universities have for years become more and more dependent on student tuition to stay solvent. Students’ reliance on debt financing to meet the rising costs of attending college has been a consistent trend. Student debt loads have increased by more than 100 percent over the past ten years, and even before the pandemic more than a million student debtors were defaulting on their loans.

In a country that has yet to fully grapple with its history of racial and gender oppression, it is not surprising to learn that those most negatively impacted by student debt are Black men and women and women borrowers across racial groups. The latter hold a disproportionate 66 percent of the total debt load, and they carry their debt longer as the result of a still-entrenched gender pay gap. Black students may have gained more access to higher education institutions since the end of World War II, but their greater access has come at a high price. The authors of “Legislation, Policy, and the Black Student Debt Crisis,” a 2020 report issued by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, observe that, “across all racial groups, Black borrowers hold the most student loan debt despite also being consistently underserved by postsecondary institutions—especially for-profit and private non-profit colleges—toward persistence and degree-completion.” As sociologist Tressie McMillan Cottom has shown, predatory for-profit higher education institutions sell at high cost a version of the “education gospel” and a fraudulent set of education credentials to students of color promising social advancement and a way out of poverty.

Student debt contributes to the racial wealth gap. According to a 2016 Brookings Institution report, “Black-White disparity in student loan debt more than triples after graduation.” Black and Latinx borrowers take on more debt than their white counterparts and have debt burdens for longer because of long-entrenched racist labor practices. Political strategist and organizer Akin Olla recently made clear how student debt exacerbates the racial wealth gap, noting that, “according to the White House Initiative on Education Excellence for African Americans, Black college graduates have an average of $52,726 in student debt, compared to $28,006 for white students. A $10,000 student loan forgiveness would wipe out one-third of the burden of the average white debtor, while doing relatively little for the average Black debtor—and this is important because white debtors already have an easier time paying off their loans.” Olla convincingly makes the case that President Biden, given his past record on racial justice issues and his complicity in creating the current crisis by supporting laws that make it impossible to wipe away student debt through bankruptcy, owes Black debtors full, not partial, debt cancellation.

Activist groups and social justice think tanks like the Debt Collective, Demos, the Action Center on Race and Economy, and the $66 Fix have played an important role in placing the student debt crisis at the center of debates on education policy in this country. The Debt Collective’s work is particularly relevant here. Born during the Occupy Wall Street movement, the group has pushed the student debt debates to the left, arguing since its inception for full debt cancellation and free public higher education. To date, the group has won over $2 billion in debt cancellation. Advisers for Senator Elizabeth Warren have stated on the record that she was inspired by the Debt Collective to take a more active stance in the debt cancellation fight. Debt Collective members were present at the press conference where Bernie Sanders and the congresswomen known as “the squad” announced the College for All program. The recent Democratic presidential primary particularly demonstrated how the work of activist groups is paying off. Every serious contender for the right to challenge Donald Trump had to have a plan to deal with student debt and the rising cost of attending college. Bernie Sanders’s College for All platform, followed by Elizabeth Warren’s recommended reforms, took these proposals furthest to the left, while Joe Biden eventually settled on a means-tested centrist approach to the crises. How the newly minted Biden administration now handles the student debt dilemma is already shaping up to be one of the most hotly contested questions of his early presidency.

As recently as ten years ago, the notion of canceling student debt was mocked as ludicrous and utopian even in some progressive circles. Those fighting for student debt abolition thus have already made important progress in the battles for hearts, minds, media attention, and policy making. Whether the debt abolition efforts will result in total victory—full cancellation of federal student debt—remains to be seen, but it does seem inevitable that something will be done, and soon.

When higher education policy experts and commentators do discuss what can be done, their recommendations are circumscribed by economic calculations, political cost-benefit analyses, and dominant ethical norms. So, for example, when one wants to make the case for full debt cancellation, one is obliged to demonstrate how full cancellation will not hurt but benefit national and local economies and debtors themselves, why it is a popular political position to stake out, and why it is the ethical thing to do. In fact, many experts argue that the case for canceling student debt isn’t political, it’s practical, given that debt forgiveness would put more money in people’s pockets and would spur investments in basic needs like housing. The calls for full debt cancellation are met on the right, when they aren’t hastily dismissed, with predictions of economic catastrophe, or they are treated as a danger to our nation’s moral compass. Normally silent on how our national debt is a product of tax cuts for the rich and bloated spending on war and military budgets, some on the right employ a hypocritical economic-ethical argument about the dangers of leaving future generations with an oversized national debt caused by student debt cancellation. They are wrong, of course. Economist Stephanie Kelton and others at the Levy Institute have shown that “the net budgetary effect (of full debt cancellation) for the federal government is modest, with a likely increase in the deficit-to-GDP ratio of 0.65 to 0.75 percentage points per year.” Centrists and some left-leaning progressives tend to rely on means-testing approaches to simultaneously address the economic, political, and ethical dimensions of student debt cancellation by claiming that a means-tested approach is best for individuals and the economy, is the safest and most pragmatic political move to make, and is the ethical thing to do.

But given that student debt cancellation clearly is an educational issue, one would think that more attention would be directed toward considering whether student debt abolition is good for education. One could reasonably expect more discussion of how cancellation, along with a robust policy that would make attending college free, might benefit the learning experiences of current and future students. Moreover, a conversation about the potential benefits of debt cancellation on future educational experiences would force us to confront how debt damaged past educational experiences. Put in simple terms, a debate on the educational efficacy of debt cancellation would force an important question: Does assuming debt for the purposes of study irrevocably harm educational experiences? And, if it does, are indebted students past and present owed reparations in the form of debt abolition?

Debt Pedagogy

My framing of debt’s effect on educational experiences derives from Jeffrey Williams’s excellent articles “The Pedagogy of Debt” (2006) and “Student Debt and the Spirit of Indenture” (2008). Both pieces flesh out an important syllogism: because education is a process by which subjectivity is shaped and because debt influences the formation of subjectivity, educational experiences funded through debt and directed toward debt service intensify the formation of indebted subjectivity.

Williams convincingly demonstrates that instead of thinking of debt as something extraneous to higher education, we need to consider debt as “central to people’s actual experience of the current university.” Making this shift in thinking leads Williams to ask what lessons debt teaches and what students learn under indebted circumstances. The provocative conclusion to these questions that undergirds Williams’s analysis is that “debt is not just a mode of financing but a mode of pedagogy,” and he highlights six specific ways that debt affects the educational experiences of those who take it on: (1) it teaches that higher education is a consumer service, (2) it influences the rationalization of career choices, (3) it promotes the formation of neoliberal worldviews, (4) it reconfigures “civic lessons” so that civic logics resemble market logics, (5) it transfigures how we determine “the worth of a person,” and (6) it imparts a sensibility or feeling. The cumulative effect of these lessons is that universities become the training grounds for producing “disciplined,” docile, and responsible indebted subjects socialized into serving the twenty-first-century financial debt economy.

The current student debt crisis isn’t the first time that debt has influenced the shape of educational experience in the United States. In what is to date the most compelling piece on how debt and education form an apparatus that shapes subjectivity, literary scholar and cultural historian Saidiya Hartman has demonstrated in her 1997 masterpiece Scenes of Subjection: Terror, Slavery, and Self-Making in Nineteenth-Century America that for ex-slaves emancipation did not mark the end of bondage but the beginning of an era of “indebted servitude.” As is well-known, ex-slaves were denied land and fair labor opportunities and subjected to gratuitous violence sanctioned, and often performed, by the state. They were simultaneously forced into debt peonage, told incessantly that they owed a moral debt to the nation that had “freed” them, and taught, through the use of conduct books and other means, how to fulfill their imposed debt obligations. Debt was both the subject of pedagogical content and a means of subjugating former slaves. Hartman describes how former slave owners, northern industrialists, and liberal education reformers in the postbellum United States worked to guarantee that ex-slaves be “transformed into a rational, docile, and productive working class—that is, fully normalized in accordance with standards of productivity, sobriety, rationality, prudence, cleanliness, [and] responsibility.” Given the historical record and the racialized realities of the current Black student debt crisis, one must take seriously the claim that student debt is but one of the many vestiges of what Hartman calls “the afterlife of slavery.”

On Miseducation

In his canonical 1916 book Democracy and Education, John Dewey argues that any truly democratic project must include a well-rounded progressive public education system. Dewey maintained that educational practices should be as democratic as possible and that education should serve as a process by which democratic dispositions are formed as people are socialized into democratic society. Schools and universities for Dewey are public democratic goods that should be easily accessible to all members of society. Put simply, in Dewey’s philosophy of education, progressive educational institutions and pedagogical practices benefit both individuals and society writ large. In a Deweyan framework, therefore, it would make no sense to limit access to high-quality education in a democratic society. Democracy and Education was widely taken up by educators across the country and spawned a “student-centered” progressive education movement. In the book, Dewey critiqued “traditional” education as being undemocratic and disconnected from students’ lives, and he sought instead to promote an educational philosophy that centered student experiences in the construction of learning experiences. Dewey’s philosophy received critiques from across the political spectrum. His work was challenged both by those who thought that he had delegitimized teacher and adult authority in education and by those who believed him to be naive in thinking that democratic relations were possible in public education settings within a capitalist society that constantly reproduces undemocratic social relations.

In 1938, writing in response to the progressive educators whom Dewey believed had either misunderstood or misapplied his philosophy of education and to the critics of his educational philosophy, Dewey penned the short but densely packed Experience and Education. Two central arguments on the nature of educative experience make up the backbone of this book. On the one hand, according to Dewey, educational philosophy is, or should be, based on a philosophy of experience. But on the other, he stresses that not all “experiences are genuinely or equally educative.”

There are, in Dewey’s view, important differences between educative and miseducative experiences. Experiences are considered educative if they meet certain conditions of growth and interaction. They must abide by what he calls the “principle of continuity of experience.” According to Dewey, every experience both takes up something from those that came before and modifies in some way the quality of those that follow. In other words, cumulatively, the quality and depth of our educational experiences change something of ourselves—and enable us to change others. Dewey notes, however, that while nearly all experiences have a certain continuity, educative experience not only depends on continuity but must also promote growth, “understood in terms of the active participle, growing.” Education, in Dewey’s view, should promote the flourishing of potentiality in a myriad of directions. Or, put negatively, education should not pigeonhole development or direct growth unidirectionally.

Stated slightly differently, educational experience meets the first criterion of being educative—promoting growth—if it responds positively to two questions: “Does this form of growth create conditions for further growth, or does it set up conditions that shut off the person who has grown in this particular direction from the occasions, stimuli, and opportunities for continuing growth in new directions?” And “what is the effect of growth in a special direction upon the attitudes and habits which alone open up avenues for development in other lines?” Asking these two questions helps make it clearer that being in debt for decades after attending college impedes “continuing growth in new directions.”

Dewey’s second principle of educative experience is “interaction.” As people grow through interaction with their environment, they also alter that environment in substantive ways. If this interactive experience between subject and environment can be labeled “educative,” it is because it creates situations for continued future multidimensional growth through continual interaction. The principal concern of the Deweyan educator is thus to create situations in which educative interactions take place. In other words, the educator’s task is to regulate the objective conditions in which experiences will unfold so that growth occurs.

What then constitutes a miseducative experience in Dewey’s view? Dewey is surprisingly brief in responding to this question, opting instead to assume that his readers understand that violations of the principles outlined above are conducive to the cultivation of miseducative experiences. It does, however, bear repeating that for Dewey not all experiences are educative—and that would include many of the experiences that are had in educational institutions that “engender callousness” or “produce a lack of sensitivity and responsiveness” to the world, school subjects, and others. Such callousness may increase efficiency and productivity in certain lines, and Dewey admits that even miseducative experiences can “increase a person’s automatic skill in a particular direction,” but if this leads to unidimensional growth—that is, growth that is primarily geared to debt service—then the “depth and quality” of present and future experiences have been narrowed rather than enlarged and miseducation has occurred, because, as Dewey emphasizes, “any experience is miseducative that has the effect of arresting or distorting the growth of further experience.”

Debt, I contend, fosters miseducation. While this is a universal claim, certain groups are affected more than others. Debt’s ability to miseducate hits historically marginalized groups hardest, both because individuals in those groups take on more debt and because they will struggle more than others to pay it back. The heavier the weight of the debt burden, the more miseducative the debt is. Acknowledging this is not to advocate for a means-testing approach to education justice, however. Debt cancellation, as the Debt Collective emphasizes, needs to be universal. If one believes that educational experiences that promote growth are good not only for individuals but also for society and democracy writ large, then one must admit that the benefits of universal cancellation potentially affect our society and democracy in a variety of positive ways. In other words, universal debt cancellation is a public (education) collective good.

Debt Miseducates

Taking a stylistic cue from Williams, I want to suggest that there are at least six ways that debt fosters miseducative experiences.

First, debt imposes upon the experience of study. For the indebted student, study is an exercise in debt-service training. Debt influences both the content and the form of study. Regarding content, students often decide a course of study or major on the basis of assumptions about its ability to enable them to pay off their debt—upward of a third of incoming college students plan to major in economics, for example, and that number grows if you include business majors. And university administrations often use such data to justify cuts to liberal arts programs in the interest of servicing university debt. Regarding form, debt often shapes rhythms of study. Students who seek to avoid as much debt as possible often pile on credit hours each semester in the hope of graduating as quickly as possible. The rationalization here is simple: the more time I take to study, the more debt I will accumulate.

The influence of debt on study becomes visible through examination of those on the other side of the pedagogical relationship: teachers. The student debt crisis is likewise a student-turned-teacher crisis. Adjuncts, lecturers, and tenure-line faculty often carry enormous debt loads that sometimes sway what they teach. In some cases, indebted professors are pedagogically “disciplined” by the debts they owe insofar as they rationally fear what might happen to them if they lose their appointments for teaching something that either invokes the wrath of their students or irks higher-ups. For example, an adjunct in an education department might take the safe route by teaching master narratives of university history rather than offer a critical approach to university studies. The cost of teaching against the grain can be debt insolvency. Thus, many faculty members become pedagogically risk averse and grudgingly “satisfy the customer” (their paying and indebted students) and their superiors by teaching what they know these parties want. This, of course, also affects student education. And as universities hire ever greater numbers of low-cost contract faculty as a way of cutting costs, it becomes ever harder for adjuncts and part-time lecturers to pay off their own debts.

Second, owed debts shape indebted people’s dominant problems and thus their thinking; the debt they owe gives birth to the problems which are generative of their thinking. Put simply, debt truncates modes of problematizing. Here, again, Dewey is instructive. For Dewey, “problems are the stimulus to thinking,” and he maintained in Experience and Education that the problems that spur thinking arise “out of the conditions of the experience being had in the present.” When an economic concern like debt is the problem in which the student is most presently engaged, that student’s problematizing is significantly truncated by the indebted circumstances in which it develops. Thus, it is common to encounter students who have clearly mapped out their educational careers in response to their current and future debt problems. What they think (or not) is influenced by the debts they owe.

Third, debt affects the interactions that students have with their educational and social environments. Debt violates Dewey’s principle of interaction in numerous ways. Not only are the campuses where students study increasingly financed by debt and therefore under constant threat of austerity, but students themselves are also forced into interactions that negatively affect their physical, mental, and emotional health. Many students, for example, live in dilapidated and overcrowded housing to keep living expenses down and make careful decisions about which textbooks to buy and which to forgo.

Furthermore, to avoid debt, and in order to pay for rising tuition costs, students increasingly spend more time in work environments than they do in study environments. When this occurs, labor relations take precedence over educational relations. The work-study balance of students in California is illustrative. According to the Student Protection Act (California Assembly Bill 393), “In 1985, California State University (CSU) students had to work 199 hours at minimum wage to pay tuition and fees for an academic year at the CSU; in 2015, students had to work 682 hours at a minimum wage job to cover those costs.” This leads three out of four CSU students today to work more than twenty hours per week.

Given these effects, it is no surprise that the fourth miseducative impact of debt on education is that students often appear to be “callous” and “unresponsive” in their coursework and academic trajectories. Undernourished, exhausted, and anxiety-ridden and trying to balance too many credit hours with excessive work hours, students tune out course material and disengage from the learning process. No one should be surprised or angered by this outcome, nor should we expect students to remain responsive to course material that has been chosen based on debt cost-benefit analysis. When debt exerts its force on the educational process it can produce a “callousness” toward subject matter not deemed relevant to the indebted life and decrease the impetus to learn anything that is not perceived to be helpful in servicing debt.

Fifth, across time and place, debt has been used as a disciplining apparatus. To take on debt is to enter into an asymmetrical creditor-debtor power relation. As political theorist Melinda Cooper scrupulously documented in her 2019 book Family Values, the gutting of public funding for higher education and political decisions to raise tuition over the last several decades are directly related to the student movements of the 1960s and 1970s. Debt is a convenient way to keep students in order. It diminishes or outright destroys the democratic impulse to challenge power in educational settings. Under the burden of debt, students are easier to control, and often discipline themselves for fear of damaging their access to both credit lines and the accumulation of credits needed for graduation. Rather than serving as experimental zones for democratic deliberation and contestation, universities filled with indebted students (and faculty) more resemble training grounds for socializing students into the creditor-debtor power relations that they encounter in the overall political economy.

Finally, debt distorts education temporalities. Debt has the dual effect of occupying the present and foreclosing on the future. Students settle on a present course of study in preparation for living a future that in many ways debt has already foreclosed. Put in Deweyan terms, the “potentialities of the (education) present,” which should take precedence, are sacrificed to a presumed debt-laden future.

Closing Thoughts

On the day that Joe Biden and Kamala Harris were sworn into office, one hundred indebted people from across the country declared a student debt strike. Organized by the Debt Collective, the strikers are demanding that Biden either use an executive order or that Congress pass a bill to cancel all federal student debt. Their strike can be framed in economic, political, and ethical terms. But the Biden Jubilee 100 debt strike should also be framed as a strike for education. A student debt jubilee would not only liberate forty-five million people from crushing economic debt burdens; it would also repair educational wrongs past and free educational futures to come.

In her essay “The Crisis in Education,” Hannah Arendt proclaimed, “Education is the point at which we decide whether we love the world enough to assume responsibility for it.” During this education debt crisis, we have a decision to make. We must decide whether we want to assume responsibility for rectifying a debt dilemma that has created one of the most pressing educational crises of our time. Canceling student debt would mark a small step toward accounting for past miseducation and building a reparative university to come. Do we love education enough to free it from the bonds of debt? How we handle the student debt crisis will say a lot not only about how much we care about education but also about how much we love the world and the people in it.

Jason Thomas Wozniak is assistant professor in the Department of Educational Foundations and Policy Studies at West Chester University. He is also the codirector of the Latin American Philosophy of Education Society and an organizer with the Debt Collective. His email address is [email protected].