The November 2015 image of former University of Missouri professor Melissa Click scowling into a video camera during a protest and yelling at a student photographer, “You need to get out. . . . I need some muscle over here,” not only captivated those working in higher education but also captured the attention of the nation. Protests have swept across campuses over the past few years, and, in countless cases, professors either participated in these demonstrations or offered commentary on the protests and their larger sociopolitical context. Clark Kerr’s decades-old reflection that “whenever there is political tension between society and the nation’s campuses, concern is likely to be expressed about the influence of college and university professors” seems to hold true today.

Despite observations from some pundits that there are “fewer public intellectuals on American university campuses today than a generation ago” and that increased specialization has fostered a culture that, according to New York Times columnist Nicholas Kristof, “glorifies arcane unintelligibility while disdaining impact and audience,” professors are in the media spotlight, and some scholars are now explicitly making the case for direct faculty engagement in a variety of other arenas. English professor Christian Weisser, for instance, argues that academics need to be “activist intellectuals” and package their intellectual work to meet the needs of diverse groups. More recently, the idea of engaged scholarship has become commonplace, with American studies professor Dennis Deslippe finding that such scholarship “is driven by political or social justice commitment.”

The emerging question is simple: How politically engaged are our nation’s professors today? With images of professors engaging in protest, public intellectualism, and punditry flooding the media, it would certainly appear that America’s professors are deeply engaged in the sociopolitical sphere. Given the education, time, and resources they often have, it is reasonable to expect that professors would be heavily engaged in political pursuits.

To gauge the extent of political engagement, I conducted a survey of more than nine hundred full-and part-time faculty members from December 2016 through March 2017—in the aftermath of the 2016 presidential election. I found that professors today are similar to other well-educated Americans in terms of their political engagement generally: faculty members do not constitute a unique group of political leaders, and faculty engagement with protests is limited. While a handful of scholars from across the political spectrum will always make the rounds on the speaking and media circuits, the professoriate as a whole is not leading any charge—liberal or conservative—despite the public fascination with characters such as Click.

Background

Few formal data exist on historical trends regarding faculty political engagement. While there are narrow case studies of particular incidents and historical moments such as Berkeley in the 1960s, survey questions on political behavior are scarce. The 2009 North American Academic Study Survey asked nothing about political behavior beyond two items about partisan and ideological self-placement. In a 2007 study, sociologists Neil Gross and Solon Simmons found that social science and humanities departments had a considerably greater number of faculty members who identified themselves as “liberal activists” than did science and engineering departments and that members of older generations were more likely to embrace that label. In his 2013 book Why Are Professors Liberal and Why Do Conservatives Care?, Gross talked about how ideological views affect teaching and the classroom—but nothing beyond that. Higher education researchers such as Martin Finkelstein, Valery Conley, and Jack Schuster regularly discuss the demands and goals of America’s professors but are silent on issues of engagement and political behavior entirely.

The only empirical work that captured any political behavior was Seymour Martin Lipset and Everett Ladd’s 1975 work based on the 1969 Carnegie Commission National Survey of Higher Education, which examined the professoriate after the tumultuous 1960s and asked directly about faculty involvement with campus protest activities. Michael Faia’s 1974 analysis of the Carnegie data found that professors “rarely become involved in campus protests” and that, at the four-year colleges and universities where protests had taken place, only six professors out of every thousand indicated that they had “helped plan, organize, or lead” the most recent demonstration on their campuses; 2 percent indicated that they had “joined in protest,” 12 percent said that they “openly supported” the most recent demonstration, 4 percent said that they “openly opposed” it, and 6 percent “tried to mediate.” Faia further noted that the Carnegie data revealed that for every faculty “instigator” of a protest, 125 faculty members were not involved in any way—“a fact that stands in sharp contrast to the usual finding of relatively high levels of activism among ‘liberals.’”

Political Engagement

I undertook my 2016–17 survey of 923 faculty members after the election of Donald Trump and during a time of unusual volatility in social and geopolitical concerns on college campuses. While no moment could be entirely comparable to the 1960s protests that were the focus of the original Carnegie study, campuses are now politically chaotic and protests are ubiquitous.

Keeping in mind the real-world measures of what political scientist Philip Converse calls “active citizenry,” I settled on seven groups of political activities—from attending rallies to posting materials online—that collectively offer insight into whether most faculty were engaging in political activities beyond voting. These seven groups of activities expand on the decades-old American National Election Studies battery of questions and are imperfect measures, given that they capture neither psychological interest nor mobilizing activities by parties and other interest groups.

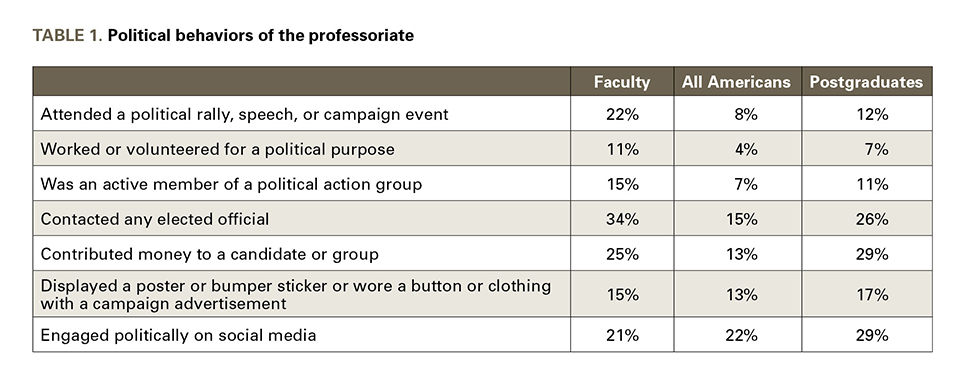

Faculty participation rates in the seven types of activities range between 11 and 34 percent. Together, the data reveal that while large majorities of professors are not politically engaged, the numbers engaged are significantly greater than in the disengaged American polity as a whole. Aside from two categories where parity exists between professors and the country as a whole—political engagement on social media (at around 20 percent) and displaying a campaign advertisement publicly (at around 15 percent)—faculty are generally two to three times more politically active than the average American.

The fact that faculty are more engaged than Americans as a whole is somewhat misleading, as it is well-known that higher socioeconomic standing generally correlates with greater political efficacy and engagement. The final column in table 1 presents engagement data for those Americans who hold postgraduate degrees. Participation jumps within this last group and is comparable with that in the professoriate. Aside from attending a political rally, speech, or campaign event and, to a slightly lesser degree, participating in volunteer work, highly educated Americans are engaging at rates comparable to faculty members. Higher rates of participation by faculty members in these areas may be attributable to the flexibility of professors’ schedules compared with those of other highly educated professionals.

Breaking down the faculty further, I found no substantive disciplinary differences in political engagement. Those in the social sciences and health-related sciences are the most politically engaged, with an average of 2.1 activities; those in the humanities, engineering and computer science, and business are engaged in 1.9 activities, and faculty in the physical and biological sciences are engaged in 1.7 activities, on average.

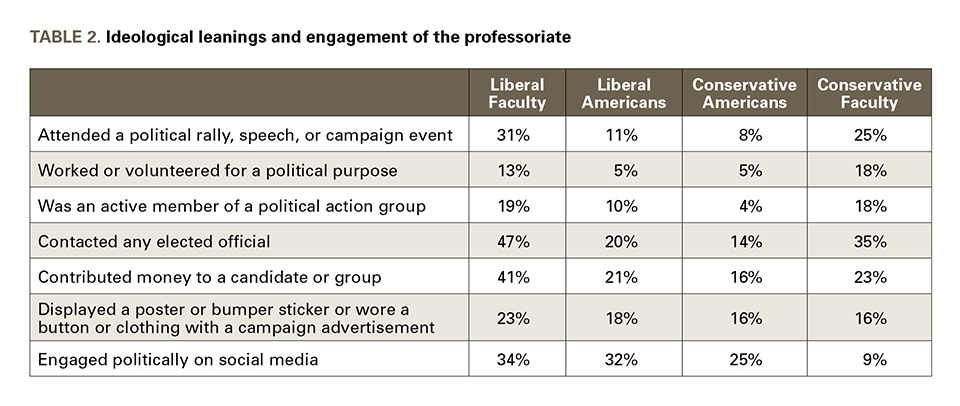

As table 2 indicates, a number of notable points surface when faculty ideology is introduced. First, faculty are more engaged than their ideological counterparts in the general population. Second, liberal faculty are the most engaged group in the sample. Across six of seven measures, liberal faculty were significantly more involved than other liberal Americans and appreciably more vocal, generous, and expressive than their conservative faculty counterparts. Third, conservative faculty are generally more engaged than conservative Americans as a whole but are engaged at lower levels than their liberal faculty counterparts. This is to be expected in many institutions, since some conservative faculty may not want to share their own views loudly because of fears of retaliation or ostracism on tight-knit campuses. Accordingly, the 9 percent rate of social media engagement for conservative faculty (compared with 34 percent among liberal faculty) is not particularly surprising.

These measures of engagement show that the loudest voices on campuses often have a disproportionate effect on how politics are perceived and covered. Liberal faculty are making more noise on the whole, and the press is regularly presenting a narrative of left-of-center engagement when, in reality, faculty collectively are not more involved politically than other well-educated Americans.

Demonstrations And Protests

In the aftermath of the violence on college campuses in the 1960s, the 1969 Carnegie study asked faculty about their views of the protests and demonstrations on campuses around the country. I have replicated the battery of questions asked by Carnegie to assess the most recent wave of campus unrest, asking faculty whether they approved of the recent demonstrations and if they were involved with the protests.

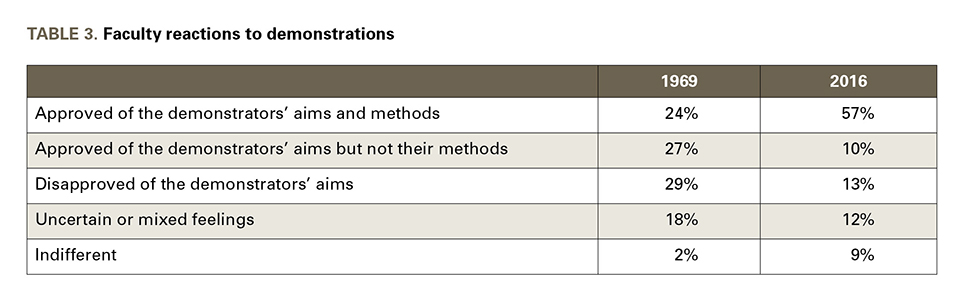

Table 3 presents data from 1969 and 2017 on faculty views regarding past and recent protests. Faculty were offered five options to describe their attitude toward the most recent demonstrations, ranging from approval of the demonstrators’ aims and methods to uncertainty or indifference. The answers show a notable shift in the overall heterogeneity of the responses: faculty in 1969 had mixed reactions to the protests, with the largest response category being disapproval of the demonstrators’ aims, but by 2016, a majority of faculty approved of the demonstrators’ aims and methods and only 13 percent disapproved of the protesters’ goals.

Regardless of the differences between the 1960s and the present, the data tell a clear story: faculty approval of protests has jumped significantly over the past fifty years, to the point where two-thirds of faculty approved of the recent protests. Not surprisingly, three-quarters of liberal professors approved of the aims and methods of the protests, while only 16 percent had mixed feelings or were indifferent. By contrast, 25 percent of conservative faculty were uncertain or indifferent and only 25 percent approved of the demonstrators’ aims and methods. Among moderates, approval of the protests stood at 40 percent and disapproval at only 15 percent. While approval numbers were lower in the 1960s, the ratios among the ideological groupings were the same. Approval of the demonstrators’ aims and methods varied by discipline, with approval at around 60 percent among those in the social sciences, physical sciences, and English; at 43 percent in history; at 37 percent in business; and at 27 percent in engineering.

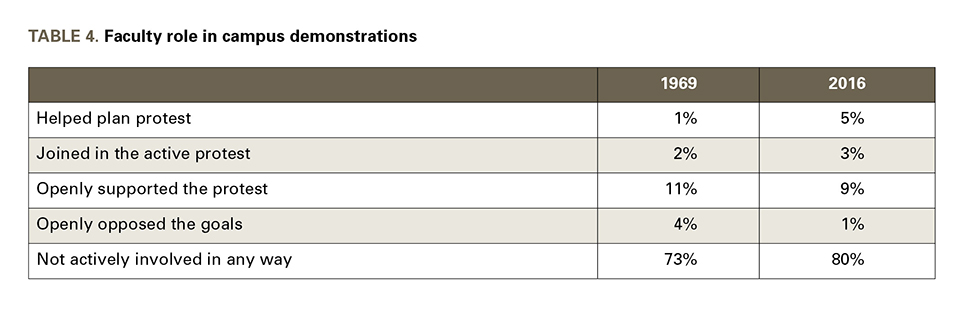

I also replicated questions about faculty connections to the protests from the Carnegie survey. Faculty today were offered a short range of choices to describe their role in the protests, which I collapsed in table 4. Notably, despite the large number who approved of the aims of the protests, 80 percent of faculty were not involved in any way. Only 8 percent were involved in the planning and execution of the various protests, and another 9 percent supported them openly. While numbers of faculty directly engaged with the protests inched up between 1969 and 2016, there was a cognate increase in overall faculty disengagement with the various protests.

Ideology played a minor role in faculty engagement, with 83 percent of conservative faculty and 74 percent of liberal faculty being uninvolved. While almost 15 percent of liberals openly supported the protests, only 5 percent helped plan and 5 percent joined in the protests. Only 4 percent of conservative faculty openly voiced support, while 2 percent joined in the protests and 11 percent helped plan protests in some way. So, once again, while liberal faculty made more noise, relatively few faculty were actively engaged in the protests. I found few differences by discipline: 75 percent or more of professors in every discipline were disengaged completely from the protests. Roughly 20 percent of those in engineering, the humanities, and social sciences supported and engaged with the protests, compared with barely 10 percent of those in the hard sciences and business. These facts, which were established during the tumultuous 2016 election cycle, show that engagement with the protests and political activities on campuses was not widespread—most faculty simply turned away.

Conclusions

With postelection stories flooding the media, it is not surprising that many believe that faculty are deeply politically engaged. Professors appear regularly in the media, and blogs featuring academic research such as The Upshot and The Monkey Cage are widely read.

The data presented above show that concerns about faculty political behavior and the political influence of faculty on the ground are overblown. Of course, faculty are generally well regarded as a group, and they certainly influence campus politics and classroom discussions. However, data collected after the election make it clear that professors are not significantly more engaged than other well-educated Americans. Moreover, faculty members are not generally leading the protests on their campuses. In fact, a greater number of professors have turned away from protests entirely today than did in the violent late 1960s. So while an editorial in the Washington Times claimed that “college campuses are filled with angry, ignorant students influenced by politically progressive and Marxist professors who don’t mind tossing a rock or two at building windows whenever a conservative speaker comes to town,” such perceptions are simply wrong. Despite the rarified position that the professoriate cultivates and the continued focus on activist professors, many in the profession are silent and disconnected from politics and real community engagement.

Samuel J. Abrams is professor of politics at Sarah Lawrence College and a visiting fellow at the American Enterprise Institute. His email address is [email protected].